I never owned a Bruce Springsteen album as a kid. All I know about him are his cartoonishly overblown 70s and 80s hit singles. I thought it would be fun to experience his records in the original order to try to understand why so many people in my life love his music.

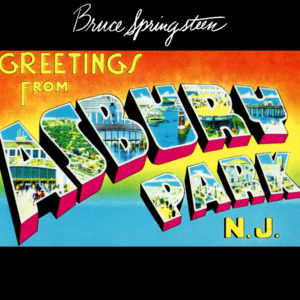

Bruce Springsteen – Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J.

released January 3, 1973

Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. is Bruce Springsteen marking his journey from teen punk to struggling adult. It captures that very moment where a young man looks past the haze of his dreams to realize he may never escape the gravity of his small town. Even in that instant he knows that soon his recognition will fade as he, too, becomes a part of the unchanging scenery that surrounds him.

It is a bleak place to live. Welcome to Asbury Park.

There is desperation here as Springsteen tries to record the true faces of the icons of his youth – a series of greasy burn-outs and painted ladies – before he joins their sad chorus. “Blinded by the Light” is both the beginning and the end of the story. It functions as a Rosetta Stone for the record. A hopscotching bass line leaps between crazed blasts of saxophone and Bruce’s non-stop artillery of lyrics as he wonders if it’s worth it to be hobbled by the simple pleasures that surround him.

There is desperation here as Springsteen tries to record the true faces of the icons of his youth – a series of greasy burn-outs and painted ladies – before he joins their sad chorus. “Blinded by the Light” is both the beginning and the end of the story. It functions as a Rosetta Stone for the record. A hopscotching bass line leaps between crazed blasts of saxophone and Bruce’s non-stop artillery of lyrics as he wonders if it’s worth it to be hobbled by the simple pleasures that surround him.

If the album was merely a time capsule of a long-since extinct mainstreet USA it would be a pleasant artifact. It is more than that thanks to the musical savvy of this nascent version of Springsteen. He fuses the sounds of his contemporaries into something kinetic and occasionally terrifying. He rambles and yowls squeakily like Dylan, treads Van Morrison’s more soulful take on folk (especially on “Spirit In the Night”), and matches Don McLean’s obsessive need to paint every corner of a story with words.

Oh, the words. Springsteen has so much to say that he rarely pauses to repeat a refrain. Songs like “Blinded by the Light” and “For You” threaten to smother your ears in sheer alliteration, growing increasingly absurd under their own lyrical weight. As it turns out, young Springsteen had yet to master the efficacy of a few cutting phrases, which means this LP yields no anthemic choruses in the mold of “Born to Run.”

You have to start here to get there. Springsteen had to empty his mind of an indelible image of his home town and the distractions of youth, as on “Growin’ Up.” That broader, metaphorical version of him is teased here, as on the elegiac “Mary Queen of Arkansas.” It is a ballad for a figure not entirely of the world he inhabited by day, but borne of dreams of a wider America, unseen.

I’ll confess, I don’t like the album very much, yet I can’t deny that it transports me to Asbury Park, circa 1973. I see a town shattered in the shadow of the Vietnam War, full of losers and junkies trying to achieve orbit on a fistful of dope and broken dreams. “Everyone’s drunk on main street, drunk on holy blood,” Springsteen intones on the cutting “Lost in the Flood.” He wonders about the anesthetized figures that surround him, “Did you lose your senses in the war, did you lose them in the flood?”

Asbury Park is not a terribly cohesive album, but it paints a specific time and place. As his contemporaries transformed themselves with each record, Springsteen honed his rangy, biographical songwriting from cascades of words into a tool that could be held by anyone. He redefined the concept of folk troubadour, at points seeming to sing with the voice of America itself like Pete Seeger before him.

Is that so different than singing in the voice of his town? Could those later songs have emerged from the lips of a man who did not come of age afraid he would never escape? That tension between stay and go, settle down or explode has been with Bruce Springsteen for his entire career. It is as much as a part of him as the alleys and main drags of Asbury Park.

And you KNOW I’m going to look forward to this feature.

I think you’ve done good job distilling the shaggy charm that gives the album such a wistful, nostalgic quality but that also makes it kid of a frustrating listen overall. Most critics will include this and its follow up, The Wild the Innocent…, among the golden-era Springsteen records, but with a few exceptions (Growin’ Up most notably), they’re not albums I compulsively return to the way I do with The River or Darkness on the Edge.

Nevertheless, the driving force of these first two albums is Bruce’s sheer enthusiasm. Listening to this album again (as I write this), the words and music carry the sheer ferocity and reckless abandon of a 23 year old from the dredges of Jersey excited at the very prospect of making an album, and consequently spilling as much paint as possible. His early discography shows the narrative of a young artist discovering his voice, taking greater chances, becoming deeper and more focused. Here, however, was a young guy filling the canvas as much as he could, in case he never got the chance again.