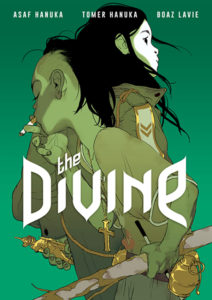

While I aspire to not judge any proverbial books by their covers, I don’t think it is such a bad thing to find a proverbial book’s cover interesting. That’s how I found so many interesting artists to listen to in the 90s – I’d just buy the CDs with the most interesting artwork.

In this case we’re talking about an actual book – The Divine. It was nothing I had heard of before from creators who were strangers to me and a publisher I don’t own a single book by. The two boys on the cover had a sort of liquidity to their poses, and they also reminded me a bit of Jamie Hewlett’s artwork for Gorillaz. Intrigued, I checked out the description, which ends with this line:

What awaits him in Quanlom is an actual goddamn dragon.

Clearly, I bought the book.

![]()

The Divine OGN

The Divine OGN

Written by Boaz Lavie with artists Asaf Hanuka and Tomer Hanuka.

#140char review: Divine from 1st Second press…a stunningly illustrated OGN w/dirt beneath it’s nails. I’d’ve liked it more if it paid off more early promises

CK Says: Consider it.

Whatever I was expecting from The Divine, I certainly got something completely else.

It’s a book that unfolds in parts, and you aren’t entirely sure what you’re reading until you are firmly in the middle. It it a story about Mark and his explosives? About his impending fatherhood? About the balance of domesticity and adventure, responsibility and risk-taking? Or, about neglect on an international scale? Or, is it really about a dragon?

Yes to all of that, even if those themes don’t play out so literally as they are introduced in the opening pages (dragon included). Instead, Mark’s trip to the fictional, wartorn country of Quanlom works as an allegory, both in his own life and for the reader. Does it all really happen the way we both witness it, with exploding body parts, clay soldiers brought to life, and fearsome dragons invisible to most men? Or, is that what Mark needed to see? The book gives a clever, blink-and-you’ll-miss it out that lets you consider just how much truth there is to Mark as our limited first person narrator.

All of that comes from a very literal inspiration – an indelible, tragic photo shot by Apichart Weerawong of a pair of Burmese twin boy turned unintended warlords, supposedly imbued with magical imperviousness. Their only magic was in occupying a dark spot in the world’s vision, a space open to intervention but impervious to compassion. (They have since departed, separated, and reunited.)

Photo by Apichart Weerawong.

There is more magic than that in The Divine, and to believe the authors’ note it is out of necessity to give a satisfying narrative to how two boys like these could be put in such a tragic position (because the real story is too terrible to replicate faithfully).

That magic is the magic of the land and of the mysterious and powerful visage of Leh, and they are both imbued with it and in in awe of it. Mark is a creature of destruction but also newly a part of creation – the second is how he reconciles one last massive act of the first before settling down in the deceivingly named Eden. (Says Rachel, “You seriously think they’d call a nice place Eden?”) He finds himself playing out this push and pull as he first negotiates with his lunkhead ex-military co-worker Jason and then later sympathizes with the tiny warlords who have aligned against him.

Divine‘s artwork is – well, I won’t say the obvious, but it’s quite perfect. Despite not looking much like it, it reminded me constantly of Robbi Rodriguez’s Federal Bureau of Physics. I think it’s mainly due to the figures and the details.

The Hanukas’ people are remarkably realistic, sometimes with a slight twist, just as Rodriguez presents a series of verisimilitudinous but mismatched caricatures. This is best expressed by a beautiful and horrific local news anchor who occupies two frames but might haunt your dreams with her broken smile. All of the faces of The Divine have that crooked truth to them. The Hanukas have captured that split-second gawkiness of a face that is handsome when in motion as well as a camera, and that makes their people shine.

Meanwhile. the surrounding environments are absolutely haunted with detail. In one panel of Mark’s living room my eyes dwelled on the bifurcated plug of a television and a unattractively-placed smoke detector. Later, in the mountainous countryside of Quanlom, their landscapes are liquid. Trees and mountains look like a sluice of melted wax, with highlights dripping across them. As the magical nature of the book increases, so does that liquid, which makes a late change back to reality feel all the more square as a result.

Meanwhile. the surrounding environments are absolutely haunted with detail. In one panel of Mark’s living room my eyes dwelled on the bifurcated plug of a television and a unattractively-placed smoke detector. Later, in the mountainous countryside of Quanlom, their landscapes are liquid. Trees and mountains look like a sluice of melted wax, with highlights dripping across them. As the magical nature of the book increases, so does that liquid, which makes a late change back to reality feel all the more square as a result.

If there is a downside to this quick read it’s that not every detail you pick up on early in the book is paid off in full. Rachel is quickly made into a round character and then left behind, though her actions are crucial to the story. A strangely compelling exchange about a photochromic set of glasses is never recalled. Jason’s cryptic obsession with Quanlom morphs into a scenery-chewing obviousness. Mark’s skill with and fear of explosives is central to the plot, but his facility with them is secondary.

None of that takes away from the experience of the novel. If anything, it will compel you to re-read it, searching for links as you parse the allegory within the allegory. You could spend weeks picking out the fine details of the artwork, but it would be a mistake to not also dissect fine gradations of meaning in the plot. T

his is not a read once and love it kind of book, but if you are willing to let a graphic novel sink in it’s the perfect choice for you.

![]()

What came before: from the Hanukas: Bipolar collected as The Placebo Man … from Asaf Hanuka: The Realist … from Tomer Hanuka: Overkill & Philosophy in the Boudoir

You might also like: Federal Bureau of Physics Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 (similar art with low-fantasy sci-fi twist on reality)