| Essentials of the Era |

| “Unwashed and Somewhat Slightly Dazed” – BBC “Width of a Circle” “All The Madmen” “The Man Who Sold The World” “The Supermen“ |

Starting in 1970, David Bowie locked into an album-a-year rhythm he would maintain for nearly the entire decade as he left behind his more folk-influenced sound on Space Oddity and prepped material for The Man Who Sold The World. With this increased pace come necessarily briefer album cycles – Bowie would be on to the next era of material even before the final singles from this LP were released.

The Man Who Sold The World frequently gets lost between retrospective adoration for “Space Oddity” (not so big of a success at the time) and the three-album glam hits-capade that began with “Changes” from Hunky Dory. This marooned album had no terrific singles of its own. Nirvana did more to promote “Man Who Sold” as a song than Bowie did in the period. The period also occupies a peculiar sonic territory, with Bowie’s pre-Spiders band more interested in sounding heavy than glamrous despite Mick Ronson’s membership in both lineups.

The result is that most latter-day Bowie fans don’t know the music from this era especially well. That makes a deep dive into it all the more interesting … and challenging! This took me over a week to digest despite already having a familiarity with the LP.

Before The Man Who Sold The World

Before The Man Who Sold The World

This era begins during the last: Bowie made his first appearance with The Man Who Sold band on the BBC on February 5, 1970, as he was still promoting singles from his second self-titled album.

This appearance was a full-length concert, though only about half those tracks are readily available today. Opener “Amsterdam” by Jacques Brel would later be recored on Pin Ups. Here, Bowie attacks it with verve, first singing in a fine theatrical baritone, but gradually growing more frenzied along with the acoustic guitar that drives the track. It’s not as though any of us are at risk of forgetting Bowie was a theatrical nerd (especially with his many alter-egos looming ahead) but it’s fun to think about how surprising this performance may have been to fans of the day. The host certainly seems a bit shocked by it.

“God Knows I’m Good” is less Dylanesque here than on Space Oddity, but its refrain is less indelible. The next sequence is lost – “Buzz The Fuzz,” “Karma Man,” “London Bye Ta Ta” and “An Occasional Dream.” We pick back up with the first of The Man Who tracks, “The Width Of A Circle.” This is a fascinating early glimpse into the track, which would grow to be impenetrable on the album. Stripped to its acoustic trappings it’s much more driving, but Bowie isn’t quite up to the howling vocal here. He warbles and cracks on the higher notes.

We then skip “Janine” and “Wild Eyed Boy From Freecloud” for a vicious version of “Unwashed And Somewhat Slightly Dazed.” Here, the lower-fi sound of the radio session focuses the track’s fury beneath Bowie’s practiced vocal. Unfortunately, there’s no remaster of “Fill Your Heart” or “The Prettiest Star” – both would be fascinating. We do get a sprawling, eight-minute version of “Cygnet Committee” that’s perhaps a bit slighter than the album cut. Bowie’s highs are not as a clear, and his lows not as resonant. Finally, the show ends with “Memory of a Free Festival,” here just prior to its release as a single. However, this is more like the LP version than the fascinating single mix, with unadorned organ until the “sun machine refrain.” (A final take on “Waiting For The Man” is not collected.)

On the whole this session is unremarkable. Bowie is not in his finest voice, and “Unwashed and Somewhat Slightly Dazed” is the only song strong enough to leave a lasting impression. Indeed, it is the band unleashed on “Unwashed” that seems to best presage the heft of the impending LP despite being still months out from its recording.

The band would return a little over a month later, already fused into a more metal stomp. They show it off on a pulsing version of “Waiting For The Man” with nothing of Lou Reed’s strut (which gets a little weary by the close). Mick Ronson, in particular, is in strong form. “Width of a Circle” has grown hugely in the intervening month. Bowie’s vocal is massive and confident, and Visconti and Woodmansey are beginning to lock into the riffing and fills that would appear on the LP without overdoing them. The song had yet to grow its epic tale of gods and demons (more on that below), so this isn’t really a definitive take on it. A plain electric guitar version of “Wild Eyed Boy From Freecloud” feels out of place even after the band kicks in after the “really you and really me” refrain.

The Man Who Sold The World – Released November 4, 1970

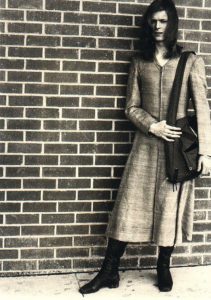

The original UK cover.

This might be a weird statement to make about a David Bowie record, but I find it hard to enjoy The Man Who Sold The World because so much of it feels insincere.

When is David Bowie ever really being sincere? He’s not known for his confessional lyrics, that’s for sure. Yet, I would propose there is an inherent honesty and weight in how he portrays many of his fantastic characters with real emotion. They matter to him, so they matter to us. Here, Bowie’s narrative creations feel like nothing more than window dressing to a squalling live band of Mick Ronson, Tony Visconti, and Mick Woodmansey, with Ralph Mace on synthesizers.

The band rocks hard – as hard as anything in Bowie’s catalog until Tin Machine. They lean into a prog-rock, proto-metal sound on this disc that isn’t so far from early Black Sabbath, doubling down on the vibe of the heaviest cuts from Space Oddity. It all sounds terrifically heavy under Visconti’s production, but it isn’t a terrific fit for a fey young Bowie who famously appears on the LP’s cover in an ornate dress. The band’s driving sound leaves little room for Bowie’s flights of lyrical fancy. His vocals are often pushed to their most shrill rock belt, with none of the nasal tone he would use to cut through the band in the Ziggy era.

Opener “Width of a Circle” shows off both the heaviness and the weakness of the band. After an appropriately circular opening riff played by all of the members together they explode! Each of them plays amazing, memorable fills, especially Visconti on bass, yet at points the song sounds like a competition between band members. Bowie’s allegorical lyrics make for fantastical prog rock, but they come off as lightweight nonsense as they compete for attention amongst the arrangement.

Those lyrics bear a deeper examination. After a crackling Ronson solo they reveal a journey to self-understanding that leads Bowie to fall into hell, entwined in near-sexual writhing with a demon god like Gandalf and the Balrog.

He swallowed his pride and puckered his lips

And showed me the leather belt round his hips

My knees were shaking my cheeks aflame

He said “You’ll never go down to the Gods again”

(Turn around, go back!)He struck the ground a cavern appeared

And I smelt the burning pit of fear

We crashed a thousand yards below

I said “Do it again, do it again”

(Turn around, go back!)His nebulous body swayed above

His tongue swollen with devil’s love

The snake and I, a venom high

I said “Do it again, do it again”

(Turn around, go back!)

It almost feels as though Bowie is apologizing for his fantastical vision by dressing it in such hard-rocking trappings. The song feels overlong at four minutes before we even get to the passage above. And it, the song’s most passionate moment, isn’t rendered with the same ferocity as the opening – it’s dressed with an almost-silly boogie blues when it should have been the peak of volcanic riffing.

The result is something fascinating but unbalanced, like a beautiful sword carried at the hip of a king that is not meant to be unsheathed in battle.

It’s easy to tag these excesses on “Width of a Circle” because “All The Madman” treads the same sonic ground with care and precision. It feels like a tidier version of Space Oddity‘s “The Cygnet Committee.” A dirge-like introduction is ferried by a cymbal ride and mellotron flourishes into thunderous mid-tempo rock complete with a harmonic guitar solo. Here, the band never swallows their leader. Bowie nearly sighs, “Don’t set me free … ’cause I’d rather stay here with all the madmen.” This is Bowie both genuine and surprising melancholy, as our narrator admits it’s better to be crazy and glad than sane and sad outside in the real world. This resigned madness is a familiar Bowie emotion. It’s conveyed perfectly here even as the song descends into chanting French gibberish at its close.

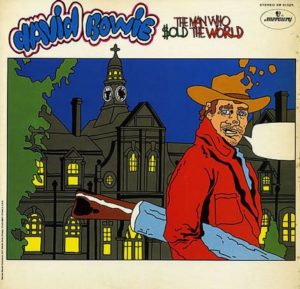

What has become the official and most widely-known cover of The Man Who Sold The World.

At this point, the album seems to be doing something significant and singular. In the span of two songs and ten minutes, Bowie has broken ground on themes of self, sexuality, and sanity, and he’s makes it sound particularly heavy while retaining his signature acoustic base.

Neither the sound nor the themes persist in the middle section of the record. This vast, doughy middle of insincerity is the core of my struggle with this album.

“Black Country Rock” is similar to the American rock sound of “Janine” from Space Oddity. It’s a little lankier, with more swagger. The band sounds sure and limber, the guitar tone is devilishly piercing, and there is a grin behind Bowie’s delivery (especially in the third verse, as he imitates Marc Bolan). You can imagine the alternate history of this heavy metal incarnation of Bowie growing alongside Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin.

This jagged arrangement had the power to speak more about the joys of madness, but it’s comprised of just one verse that feels more like an interesting collection of interesting sounds than a distinct a song (“Pack a pack horse up and rest up here”).

A later incarnation of Bowie could turn “After All” something remarkable. With a heavier swing it could be a pint-swaying drinking song. A more menacing arrangement would give it a seething, sinister bent. Without that drive it’s overburdened by its clumsy lyrics, like: “I sing with impertinence, shading impermanent chords, with my words.” This is the wordy, self-conscious Bowie of the prior two albums. The balance between Bowie’s low baritone and falsetto isn’t right, as it would be later on work like “Golden Years.” Instead, it sounds comedic.

“After All” closed the A-Side of the album on a pessimistic note. Paired with “Saviour Machine” as the opener of the B-Side, it feels that Bowie is already issuing a gentle rebuke of the free love, carefree feeling of “Memory of a Free Festival.” He even draws a direct parallel to the free-floating white balloon and sun machine party of “Festival”:

We’re painting our faces and dressing in thoughts from the skies,

From paradise

But they think that we’re holding a secretive ball.

Won’t someone invite them

They’re just taller children, that’s all, after all

The B-Side of the album holds up a mirror to the A, starting with missteps before approaching the more remarkable material. “Running Gun Blues” is an unfortunate mess. We find the band in tight form as on “Black Country Rock,” but Bowie squealing a lumpy story of a Vietnam soldier gone berserk. It feels more like a political version of the silliness from David Bowie than a contemporary of the rest of this material. It’s also one of his weakest vocals. “She Shook Me Cold” is a wheezing knockoff of “Whole Lotta Love.” It’s catchy and might have been a deserving single, but hopelessly flimsy compared to the rest of the album.

The band fights against (or, amongst) itself less on the similarly overwrought “Savior Machine.” Bowie joins them in working himself into a froth with operatic baritone vocals on the refrain, filled with wide swaths of vibrato. It is altogether so grand it feels like a years-early outtake of the Orwellian Diamond Dogs (“You can’t stake your lives on a Saviour Machine”), but it also returns to the themes of logic versus madness of the opening duo of songs.

When the droning, three-note riff of “The Man Who Sold The World” cuts the air it’s immediately apparent that we’ve arrived at something very different. It’s not only notable for being the title cut of the disc or the song later made as famous as any other Bowie original. It stands apart from the rest of the LP sonically, as well. It’s by far the lightest cut on the disc. The elements feel as though they would be a better fit on the prior LP, although they form a gestalt moreso than the arrangements on either Space Oddity or this release. The almost-lounge vibe of brushed drums, guiro, and acoustic guitar, the phased effect on the vocal, the laser-fine electric guitar tone – each is distinct in the mix, yet they don’t compete for attention as the band’s playing does elsewhere on the disc.

There’s also the subject matter of a benevolent post-messiah – a god amongst men who chose to depose himself:

I spoke into his eyes

I thought you died alone, a long long time agoOh no, not me, I never lost control

You’re face to face With The Man Who Sold The World

The cover was reissued when Bowie’s dress was considered too risque. Despite clearly being from the next era, this cover remained the one in circulation until the 90s!

The message is intriguing. Instead of heavy metal wrestling with gods and logic, instead we casually meet a man who gave everything away with a natural ease. As he shares a conspiratorial handshake with the narrator, he seems to pass something else along with his firm grip – a certain electricity, yes, but also a sense of connectedness. Now the singer understands, and the final chorus reflects that with the revision to “we never lost control.” There will be no wagers on messianic machines or battles of logic with gods. The easiest thing to do is to give it all away so you can never lose your grip.

If there is a suggestion of a glimpsing a past life in “Man Who Sold The World,” it is the “The Supermen” that expands on that lost history. It is one of Bowie’s most straight-up fantasies of all time, on par with “Wild Eyed Boy From Freecloud.” It neatly matches with the engorged god he wrestles in “Width of a Circle,” as he describes a lost race of lumbering gods policing the Earth.

The “strange games they were playing” evokes for me the images of Plato’s Symposium, later put to song in Bowie descendant Hedwig and the Angry Inch. The ominous chanted backing vocals, throbbing bass, and tom-heavy drumming perfectly evokes massive feet trundling across the earth. Yet, even as Ronson unleashes a storm of distorted electric guitar, Bowie’s vocal floats above it – the mix favors him, and he’s singing in a lower and more powerful range than elsewhere on the LP. Bowie slowly climbs a scale above the lumbering rhythm section and deluge of guitar until the apex, a distinctive howl on “a supergod cries!”

There is no rule in music that you must write songs that form a cycle, or even that sound like they belong together. Bowie would later master this art, and here we witness his discovery of it. So how does this album not succeed in its mission? In aggregate, it is the sound of Bowie not at the controls of his own destiny, which is a mode that he’d repeat only sparingly during the rest of his career. Indeed, writing on the era emphasizes his disconnection and absenteeism from the studio. That’s at odds with the consummately prepared technician Bowie we’d see for the rest of the 70s.

It isn’t surprising, then, that Bowie’s band is so often in the spotlight here – and, not in a way he would later encouraged in his songwriting. It’s as though he had some portion of a vision for where the record could go but couldn’t quite fulfill his own lofty goal. That is how this album lacks in sincerity – it doesn’t feel whole.

Even if I consider the effort to be a net failure, an ineffable magic remains. Bowie broke ground here that he would continue to mine for forty years more. There is still the title cut, still that fey image of Bowie on the cover, still his evolving philosophic opinion of big brother versus free will and the disaster that lies in wait on either side of the spectrum. There are sgods who are men later in Bowie’s career, but that parting shot of “a supergod dies” is something we would never see again – Bowie retiring a race of elder gods to shift his focus to the kind of gods who we could see, touch, and fuck.

“Holy, Holy” b/w “Black Country Rock” – Released January 15, 1971

First, note that the “Holy, Holy” generally associated with CD releases of The Man Who Sold The World is actually a later recording from 1971 that was even later released as a Diamond Dogs B-Side.

First, note that the “Holy, Holy” generally associated with CD releases of The Man Who Sold The World is actually a later recording from 1971 that was even later released as a Diamond Dogs B-Side.

As for the original 1971 single, two things are obvious: why it was chosen over album cuts and why it was not a hit.

Considering hardly anything on the disc had a proper chorus, there weren’t many other options for singles. On the other hand, this song is a mess. Somehow it both gallops and drags.

The band doubles down on the confusion of “Width of a Circle.” Everyone sounds as though they are playing a different style of song without listening to the others. The bass suggests a chugging four-on-the-floor rhythm while the drums sketch a military march. The electric guitar mostly follows Bowie’s vocal, while the acoustic has a sort of Flamenco flourish to it. Bowie sings in his penetrating higher range and there is a peculiar pattern of lines growing higher and higher before the melody drops on the chorus hook.

This is an interesting indicator of Bowie’s demos of the period. Altogether, it has a very Ziggy mid-album feel to it, and not just for the “lie lie lie” refrain’s similarity to “Starman.” In fact, he was already penning much of the Ziggy material, but he hadn’t worked out the magic Spiders formula for the songs. This is evident on the impending Arnold Corn material, as well.

“Moonage Daydream” b/w “Hang On to Yourself” by Arnold Corns – Released May 17, 1971

Pictured here is Freddi Buretti, Bowie’s friend and fashion designer, who was feted as the lead singer of this imaginary band.

In a bit of slight-of-hand, Bowie circumvented some label woes by launching a mysterious parallel glam act, Arnold Corns, which was actual his own band with him playing hype man. Not so different than the Ziggy Stardust formula, if you think about it. He gifted this act with two of the best Ziggy-era deep cuts, “Moonage Daydream” and “Hang On to Yourself.”

Neither had developed into their future indelible versions. “Moonage Daydream” doesn’t even have many of its final lyrics intact, and Bowie sings it all in a howling legato that has none of the deadpan sexiness of the final version. The song is primarily acoustic save for the solo, which alternates with each verse instead of coming before a final refrain. There is no epic Mick Ronson finale.

“Hang On to Yourself” is similarly neutered by odd performances choices, though it’s much closer to its final form than “Moonage.” It is crazy to think that if Bowie hadn’t pressed on through Hunky Dory and gained some notoriety that these might be the only two versions of these songs we know – especially considering that the Ziggy version of “Moonage Daydream” is one of my favorite songs of all time!

The famous acoustic piano demo of “Lady Stardust” which later appeared on reissues of Ziggy Stardust may also originate in this era. It’s remarkable how fully-formed it is, perhaps owing to the gestalt of piano arrangement rather than contributions of the band.

(Some Bowie biographers would argue with my placement of this single, as Bowie didn’t commit any Ziggy material to demo until after the promotional cycle of Man Who Sold The World. However, it occupies a space of uncertainty between his record contracts, before there was promise of Hunky Dory being committed to record and was recorded before any Hunky Dory material was debuted live on the BBC. For my purposes, it slightly predates the formal start of the glam era, rather than kicking it off.)

Other Material

An early demo of “The Supermen” is not as ominous, with incongruous peals of electric guitar solo, while a demo of “All The Madmen” is huge and hard-rocking – nearly verbatim to the LP. The mono single of “Madmen” is a bit of a mess, showing how importing the transition to stereo was to Bowie’s emerging sound.

An early demo of “The Supermen” is not as ominous, with incongruous peals of electric guitar solo, while a demo of “All The Madmen” is huge and hard-rocking – nearly verbatim to the LP. The mono single of “Madmen” is a bit of a mess, showing how importing the transition to stereo was to Bowie’s emerging sound.

“Lightning Frightening” is a acoustic sketch included on some reissues of Sold The World that could have gone in the direction of “Black Country Rock,” but it was recorded along with Hunky Dory material.

##

I came away from my critical listen with a much deeper appreciation of this LP, and a tendency to sing “Black Country Rock” on loop for hours on end. Even if I’m not a major aficionado of this period of Bowie’s early work, I can concede how important it was for his future – both sonically and in helping him gain some traction in the American market. In a career of transformations, the wake of this era lead Bowie to undergo one of biggest reinventions and most-prolific periods.

That means I’ll have plenty to talk about in my next post, where I focus on a lifelong favorite, Hunky Dory.