I’ve always loved the risk/reward of a blind buy.

I’m not talking about buying a new appliance sight unseen here. I’m talking about more subjectively judged products, like music you’ve never heard or heard of or a dish of unfamiliar food of which the only detail you are only certain it is not poison.

If we always seek out what we know and have been recommended, how can we ever be surprised? Some of my favorite albums came from picking something up purely because of a band’s name or their photo, and the vast majority of my indie comic collection came from trying something without knowing a thing about it other than the aesthetics of a cover image or a few lines of promotional copy.

(How sure can you be about art until you consume it, anyway? Did that dance about architecture really tell you how great the building would be?)

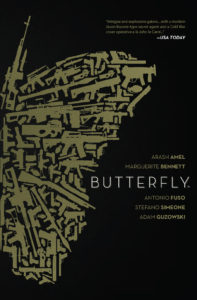

That’s nearly all I had to go by on Butterfly. I had read scripter Marguerite Bennett as a co-author with a major favorite, Kieron Gillen, but that didn’t speak much for her on her own. The cover image is stark – the shape of an olive butterfly on a black background formed by the silhouettes of dozens of guns.

There was something about it that made me want to own it.

There was something about it that made me want to own it.

Butterfly

Collects Butterfly #1-4. Story by Arash Amel, script by Marguerite Bennett, illustrated by Antonio Fuso and Stefano Simeone with colors by Adam Guzowski, lettering by Steve Wands.

#140char review: Butterfly: an icy spy tale that doesn’t bother to wash the blood from its hands. A less touchy Alias or a less fanciful Mind MGMT. Just okay

CK Says: Consider it.

Butterfly is not at all as delicate as its namesake. That goes for both the book on the whole and the main character, for whom its an alias.

We’re dropped into a mission already in progress with Rebecca Faulkner AKA Butterfly, and from the get she seems like more of a chameleon than a butterfly. She seamlessly slides into character for a dead drop and is just as facile in her initial exfiltration. However, when she discovers her routine contacts have all been disconnected she is forced to rely on a failsafe that puts her on a path to intersect her retired spy of a father, long since disappeared from her life.

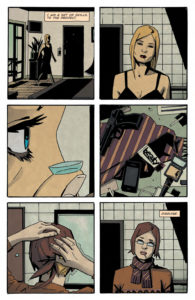

Something I’ve begun to appreciate both Marguerite Bennett both here and in other work is not only the efficiency of her language but the efficient placement of her writing. She is unafraid to let the artwork tell the story before remarking on it, even though here the art does not always have enough motion to fulfill the promise.

Antonio Fuso’s work has a lot of hard edges, and the occasionally blocky characters don’t always portray movement enough to make up for Bennett’s silences. The latter portion by Stefano Simeone is more fluid and engaging, with sketched edges left rough to imbue his characters with vibration and life. Adam Guzowski’s colors are noticeably strong throughout – I felt he used a lot of subtle changes in hue and saturation to soften Fuso’s pencils, whereas he felt extremely organic over Simeone’s looser art. (Covers by the extraordinary Phil Noto will leave you longing for his work on the interiors.)

The net result is a number of jarring scenes with small, brutal details presented with an utter lack of apology. And, while I didn’t always enjoy the aesthetic presentation, it’s that brutality that makes this book so compelling. Rebecca wants to second-guess her father’s long term actions, yet her own choices range from obviously bad to terrifyingly ambiguous, leaving the consequences to our imaginations. Despite the constant tease of familiar reconciliation, there’s no hard edges gone soft like in the frequently tearful JJ Abrams’ Alias, or soft spots becoming blind spots like in Matt Kindt’s fanciful but cutthroat Mind MGMT.

The net result is a number of jarring scenes with small, brutal details presented with an utter lack of apology. And, while I didn’t always enjoy the aesthetic presentation, it’s that brutality that makes this book so compelling. Rebecca wants to second-guess her father’s long term actions, yet her own choices range from obviously bad to terrifyingly ambiguous, leaving the consequences to our imaginations. Despite the constant tease of familiar reconciliation, there’s no hard edges gone soft like in the frequently tearful JJ Abrams’ Alias, or soft spots becoming blind spots like in Matt Kindt’s fanciful but cutthroat Mind MGMT.

Yet, like Mind MGMT, this is a fractured narrative whose proper structure you must intuit because it is never spoken. David’s story moves backwards in time from his intersection with Rebecca, but it does so clumsily – not in digestible scenes, but single pages simply reversed in chronology despite the forward motion of David’s narration. While it’s appropriate jarring and mysterious, as we circle the origin point of David’s story it seems less and less important – the pea under a mattress amplified over the distance of time.

The wider brutality of this book is the distance between us and the characters. We never meet a version of Rebecca we can care about – only a spy on the run. I’m all for skipping the foreplay of a script and starting with the action, but the result is that she comes off as flat as we’re expected to engage emotionally with her father instead.

Butterfly was satisfying to finish reading, because at the end of its carefully fractured narrative so many details click into place. However, it fails my litmus test for cleverly structured narratives – it’s dull on re-read. Having the details up front breaks any fascinating spell the book held over me.

That means the beauty of this book is in the eye of the beholder. Will you be satisfied by a slightly challenging narrative that’s part visceral spy-vs-spy and part geo-political intrigue if it’s actually quite plain upon review? If you’re seeking a more enduring riddle, this isn’t your book.

Even as I struggled to stay engaged with David’s side of the story, I ended my read in appreciation. Amel and Bennett have accomplished a delicate slight of hand, tricking us into looking for a larvae exploding into something beautiful when instead we’re meant to be carefully sensing the subtle flap of wings that creates a hurricane of senseless violence later.

(It did not escape my notice that Archaia’s matte-finish hardcover is well-constructed and pleasant to hold. Archaia’s an imprint of Boom Studios, but where Boom’s trade paperbacks can fell blocky and inflexible, Archaia’s graphic novels are objects of note and hefty.)