As a kid, I never wanted to be in a boys’ club and was always jealous of anything that was exclusively “girls only.”

I can recall many instances of this. Riding in the car, my mother tried to convince me that I might enjoy joining the Boy Scouts. “But, they’re all boys,” I replied, my rejection implicit. Later, when my female friends were allowed to sleep over together after parties while males went home, I rebelled. “Why shouldn’t I be allowed to stay over?” I raged. “They’re all of my best friends!”

It was hard for me to understand the power of either gendered space because, upon reflection, I did not feel strongly aligned to the idea of my maleness. There was nothing about it I particularly wanted – not the strength, or the camaraderie – because I did not have any evidence in my life that maleness could be good or worthwhile. I hated the idea of being a member of the boys’ club. If all you know about being a boy is bullying and irresponsibility – if the only masculinity you witness is toxic – then why would you want to access it?

That’s not to say I was desperate to be a girl. I liked to wear nail polish and own pink things because they were pretty, not out of a sense of gender dysphoria. Upon reflection, I think the idea of a gender continuum , or even simply a third gender, would have been powerful for me to be able to identify with at the time. (So would have a positive male influence, but I think the former would have been more accessible than the latter.)

Instead, I counteracted my boyness by idolizing female influences, none more than Wonder Woman – the only superhero that mattered to me even though Spider-Man shared my name.

Thirty years later, I can appreciate my ability to define my own maleness and that my gender role or expression does not define my gender identity. I also appreciate the power of single sex spaces in certain contexts. At RJ there was a recurring Ladies Night, were all the women would get together for dinner or drinks. Of course, I wanted to attend – these were all my friends out together! Yet, as women in tech, those friends shared an important, connected experience, and even as the most well-meaning male I might interrupt the ability to share that. Also, there may be women who don’t appreciate or benefit from that shared, female-only space.

Now this is a part of my story. Even when I’m accidentally or tacitly included in a boys’ club or male privilege, I don’t experience it in the same way as my peers.

I’m happy about that. I think it’s powerful to be able to access some piece of otherness to influence your viewpoint when you are in the majority. It doesn’t make you The Other, and you still have a lot of work to do to understand the experience of someone who prohibited from enjoying the club or the privilege, but it means you can see outside of your cave into the wider world of sunlight outside.

Oh, hey, and we’re here to review a comic book.

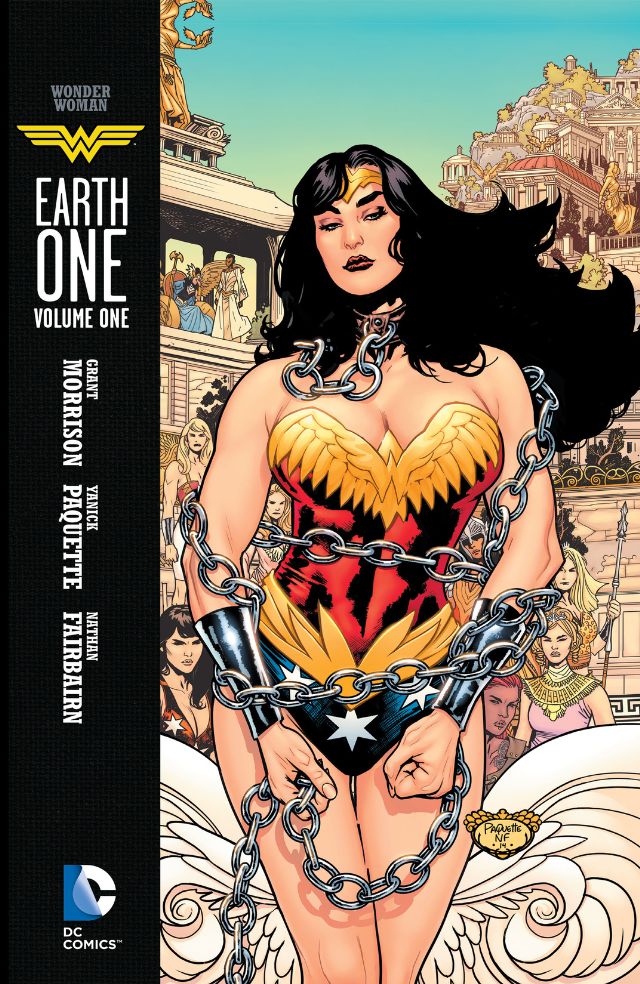

Wonder Woman: Earth One

Wonder Woman: Earth One

An original graphic novel written by Grant Morrison with line art by Yanick Paquette, color art by Nathan Fairbairn, and lettering by Todd Klein.

#140char review: Wonder Woman: Earth One is Morrison’s reverent update of a sensational origin, adding nuance in all the right spots.

CK Says: Strongly Consider it.

Wonder Woman: Earth One is a reimagination of Diana’s origin that is mostly about internecine Amazonian mother-daughter drama – exactly as it should be.

At first blush, a reimagination seems entirely unnecessary. Creator William Moulton Marston was a PhD in psychology who intentionally grounded his character’s 1941 genesis in feminine power via consultation with his pair of female partners. In Moulton’s version, Wonder Woman was crafted from clay without the seed of a man, had the proportional strength of 100 men, and lived in an island enclave of Amazon sisters. There seems to be little to improve upon for the modern day.

Grant Morrison begs to differ. Both Batman and Superman have had their own wildly popular Earth One reimaginations that are a shade different than their original beginnings. Having already written both characters solo (well and poorly, respectively), Morrison turned his eye on Wonder Woman. He would have his run on this – the third of DC’s holy trinity of heroes – in miniature format by delivering her Earth One origin tale.

Both Marston and Morrison start by tweaking the fate of Hippolyta of Greek myth, who typically winds up married or slain as a result of her role in Hercules’ ninth labor. Marston cast her as taking on a mantle of shame to make amends with the goddess Aphrodite for her capture by Hercules, which explains the Amazons’ seclusion as well as their symbolic bracelets. Morrison prefers Hippolyta as a rebel, who retaliates against Hercules and therein finds the motivation for the Amazon’s advanced but sequestered society.

Morrison’s take on Hippolyta’s subjugation at the hands of Hercules is illustrated by Yanick Paquette in a graphic, unsettling depiction in the opening pages of the book. Every time I page past it I question if it needs to exist in this story, even if Hippolyta turns the tables a few pages later. Is unsettling artwork inherently bad despite its context? And, in the case of Marston’s creations, is it so bad to push past his kink-influenced motif of ropes and chains to display the horrific reality of subjugation that he depicted only by showing light BDSM? This passage may sour you to the entire book, yet I believe it’s here to do anything but titillate.

The Paradise Island that subsequently blossoms under Hippolyta’s rule is a technologically advanced utopia that still possesses the brutal underpinnings of its origins. It’s into this society that Wonder Woman is born – or crafted – as Diana, daughter of Hippolyta.

The Paradise Island that subsequently blossoms under Hippolyta’s rule is a technologically advanced utopia that still possesses the brutal underpinnings of its origins. It’s into this society that Wonder Woman is born – or crafted – as Diana, daughter of Hippolyta.

Diana is uncomfortable in her idyllic surroundings. She is ever the royal daughter, held apart from a group of eternal peers and sometimes lovers. She is gifted with both strength and intellect, but is unable to express either fully. She was purposefully sculpted from the clay of her isle’s shores, yet as a grown woman she feels like something is missing. She wonders if there is more to life than this eternal girls’ club.

This is drawn directly from Marston’s origin and it’s perhaps Morrison’s most masterful move. We understand completely why Diana must rebel against the rules of her mother’s tournament, here recast as a traditional, celebratory farce rather than a contest of who can depart for the outside world. (Even with the best intentions, Marston’s tale still used men as a motivator.)

That Diana’s rebellion coincides with Steve Trevor crashing onto the island is a coincidence that fuels her determinedness to leave her paradise. Morrison pens her motivation to aid Trevor as platonic compassion for a man despite their differences rather than the romantic love (or, at least, adolescent obsession over the course of two panels) of Marston.

Hippolyta brands the world beyond her shores as the domain of men, but that is an act of propaganda. She attributes anything less than her matriarchal ideal as the work of men. Diana doesn’t want to leave because of the allure of man, but because of the absence of her mother’s smothering matriarchal rule. “I’m tired of playing the same role forever and ever,” Diana rages at her mother. “There’s a bigger world. … I want to be my own person!” To Diana, Hippolyta has become the very thing she herself despises – even going so far as to bind her daughter in chains!

The image of Wonder Woman bound is chains is a powerful one – Marston knew this, and Morrison does too. At this point in the story, Paquette is clearly hinting at titillation, since that was a part of the inspiration for the various forms of bondage in Wonder Woman. Again, images like the cover might induce discomfort for the modern reader, but this is as straight as a read on Marston as any aspect of Earth One.

I’m never sure what to think of Yanick Paquette’s art. The angular slant of his beautiful faces and his strong black inks are evocative of Terry Dodson, but his willingness to dwell in heavy shadow sometimes hints at Mike Deodato. That both men were past Wonder Woman artists of note is a plus. Yet, both they and Paquette are known for curvaceous, conventionally beautiful comic women.

Paquette’s take on the Amazons is relatively modest by comic standards, but still replete with a generic group of large-chested body-types (save for Beth Candy, drawn as a Cheshire Cat Rebel Wilson). Yes, the Amazons are paragons, but must they all be so very similar and pleasing to the male gaze? Even in a society where everyone was in their best possible fitness, wouldn’t some be more muscled, masculine, or slim, among other variations? His Diana is a pinup girl whose cleavage grows less demure as the tale unfolds, but she is also somewhat well-muscled (though not as statuesque as rendered by Cliff Chiang in his recent run).

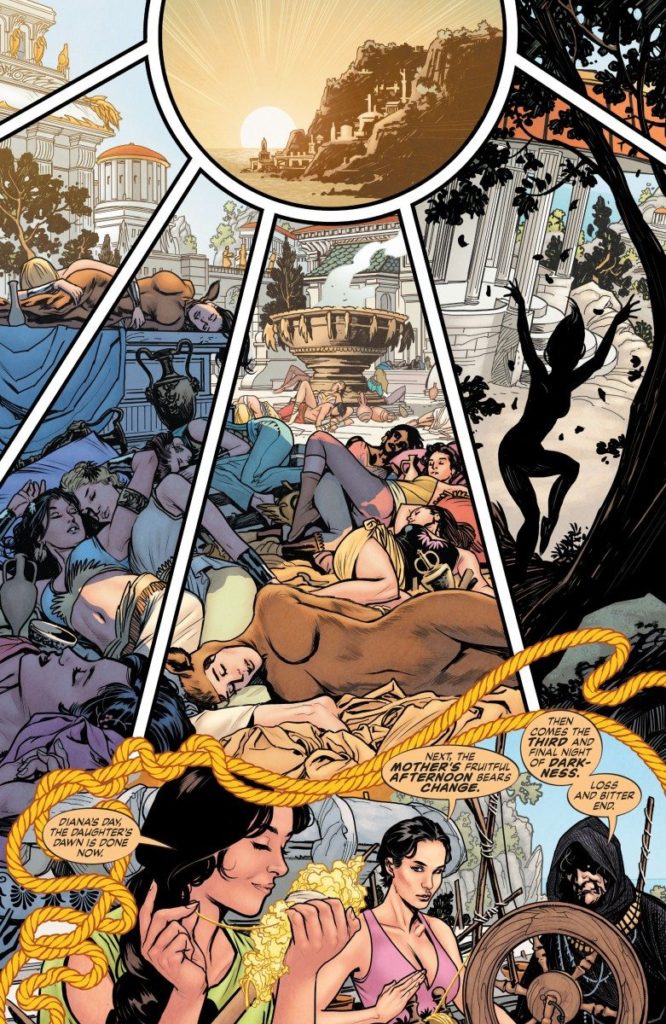

Even if you’re not bothered by any of that, Paquette’s obsession with full page spreads and eschewing conventional panel framing makes the narrative occasionally hard to follow. These tricky structures often do not flow well. His avoidance of typical panel-based layouts means single pages are a mess when they face each other (which is “always” in this book, since it does not have ads), since you’re never sure if they connect with each other. His blending of the past, the present, and a removed trio of Furies all framed by the magic lasso is a tangle.

Even if you’re not bothered by any of that, Paquette’s obsession with full page spreads and eschewing conventional panel framing makes the narrative occasionally hard to follow. These tricky structures often do not flow well. His avoidance of typical panel-based layouts means single pages are a mess when they face each other (which is “always” in this book, since it does not have ads), since you’re never sure if they connect with each other. His blending of the past, the present, and a removed trio of Furies all framed by the magic lasso is a tangle.

I know the emphasis was likely on delivering a book of impeccable beauty and mainstream appeal, but I cannot help but imagine the results as drawn by a less standard “comic book” looking artist like Phil Noto or David Aja, or a marquee female creator such as Emanuela Luppachino,Val Staples, Sara Pichelli, dreamy illustrator Stephanie Hans, or even the venerable Colleen Doran.

Nathan Fairborn’s color art is bold, but restrains itself from the plasticky gradients, reflections, and flares that often plague DC titles. His subtle blending of flesh tones to suggest depth and facial expressions is wonderful, although he gives his characters’ skin a glow that doesn’t always translate to darker-skinned characters.

I expected more of a difference of palette between Paradise and the real world, but Steve Trevor’s hospital blanket is the same royal blue as Hippolyta’s cape! Is this intentional parallelism of the fantastic and the everyday, since the fantastic is routine to Diana?

(All three of those creators – as well as letterer Todd Klein – are men. Morrison wanted to create this work, so his gender was set at the start, but it is a bit surprising to see an all-male team tackle Wonder Woman in the present day. Even in 1941, Marston had his female companions ghost-editing at his side.)

Morrison handily retreads Diana’s first visit to the man’s world with less awe and more miscommunication – and even disgust. Diana is aghast at their rudimentary technology, their violent whims, and the way they let their infirm wither away in hospital beds. She’s also alarmed by the state of Beth (Etta) Candy’s plump body but, well… you’ll need to read that exchange for yourself.

(Candy’s best comment? It’s hard to choose, but I loved “Amazonia has Class Bitches, too? That’s a bummer. Kinda spoiled my fantasy.”)

This tale deftly curves back upon itself, playing out the mother-daughter drama back on Paradise Isle as a closing parentheses to Diana’s adventure to the outside world. Ultimately, Morrison’s biggest revision to Wonder Woman’s origin results from Diana turning the tables (or, actually, the chains) on her mother. I won’t spoil this pivotal moment except to say that it does not take an obvious alternate route from the original.

As a whole, Wonder Woman – Earth One is most remarkable in that it deepens Wonder Woman’s beginnings rather than revising them. It imbues Diana with purpose and power and makes Hippolyta a more dynamic character. Morrison is at his most restrained and throws in nary a sci-fi non-sequitur, which makes this reading experience unlike his Superman and Batman.

Is it a sign that he feels Diana is a rare hero who has already been done right?

No matter the motivation, and despite some concerns on the art, Wonder Woman: Earth One is a must-read for both the lifelong Wonder Woman devotee or the casual fan. It is challenging and not always satisfying update, but it is remarkably nuanced. And, above all, it is reverent to Marston’s legacy and to Wonder Woman’s status as the world’s most iconic female hero.

(For a review more grounded in feminist theory, see a strong writeup from Comic Alliance.)

[…] the past two days, she’s completely obsessed with it. And, well, Wonder Woman was my superhero gateway drug, so I’ve been over the moon to see her carrying the book everywhere she goes. Thus, today […]