Today, Marvel and writer Brian Bendis broke the news via Time Magazine that at the end of the currently-running event “Civil War II” the mantle of Iron Man will be taken over by a 15-year old black MIT student named Riri Williams

(This  is a major shocker, because the vast majority of fans assumed Riri’s introduction in the pages of Invincible Iron Man (visit the guide) – where she was reverse-engineering Tony Stark’s armor – was a set-up for her to take over the mantle of War Machine. Rhodey has become unavailable to carry that title due to the events of Civil War.)

is a major shocker, because the vast majority of fans assumed Riri’s introduction in the pages of Invincible Iron Man (visit the guide) – where she was reverse-engineering Tony Stark’s armor – was a set-up for her to take over the mantle of War Machine. Rhodey has become unavailable to carry that title due to the events of Civil War.)

Riri Williams as Iron Man is a very good thing. We do not have enough female heroes or heroes of color, and to see a that in a character who is both as she takes over the mantle of ostensibly Marvel’s most popular single hero outside of Spider-Man is a huge, visible step not only for Marvel comic readers, but for their film fans who this news will surely reach. To have Williams also be a female super-scientist when Marvel generally boasts only a handful is even more wonderful.

(The most prominent female geniuses of Marvel are Kitty Pryde, who is frequently shown to be nearly as genius as Beast; Valeria Richards, whose preternatural intelligence is partially attributed to super powers; the new Moon Girl; and Mockingbird, an oft-forgotten PhD) .

So Riri Williams as Iron Man is a good thing, right?

On the face of it, yes. Inclusion means representation. I love reading books about heroes that are women, and so does my daughter – also a girl of color.

However, there are some aspects of this character choice that have given some fans and critics pause, which I’d like to discuss here – three in particular. I’m very interested in your input. (Edited to add: Here is a post with similar critique from black writer Son of Baldwin, Here is another from black female nerd BlerdGurl.)

![]()

1. Minority legacy heroes are only useful until the original makes their return; then their marginalization can be worse than the average minority hero.

“Legacy Heroes” is a term applied to heroes that are the replacement or junior version to their original heroes. They are sometimes used by creators as an opportunity to change the gender or race of the character bearing the main mantle.. The easiest examples to give are from DC comics (Superboy, Batgirl, Wondergirl, etc), because Marvel simply isn’t known for this practice outside the past few years.

Let’s stick with Marvel, for the moment. For a brief time in the 1980s, Tony Stark could not serve as Iron Man and Rhodey Rhodes took over the title. Rhodey is the best possible example of a Legacy Hero – he was a dynamic, well-developed character long before he became Iron Man, and that means that he was able to continue to be featured even when Tony Stark returned.

As War Machine, he’s lead his own title on many occasions (though they are usually short-lived) and he’s and been a significant character in both comics and now films (though he’s frequently sacrificed as a narrative reason to make Stark feel bad, as has happened twice this year alone).

As War Machine, he’s lead his own title on many occasions (though they are usually short-lived) and he’s and been a significant character in both comics and now films (though he’s frequently sacrificed as a narrative reason to make Stark feel bad, as has happened twice this year alone).

His time as a Legacy Hero made him more visible, but after being Iron Man he didn’t stay an A-level hero. The white guy bumped him.

Another terrific example is the relatively new Ms. Marvel, the Pakastani-American Kamala Khan (visit the guide). Kamala is a wonderful analog to the original Spider-Man as a new, unsure hero, and Carol Danvers is very unlikely to ever retake her “Ms.” hero mantle now that she is officially Captain Marvel.

Her books sell ridiculous amounts of copies and have been nominated for Eisners. She’s now an Avenger. Things are going well … but we’re only in year two.

There are examples that don’t go as well. At the end of the comics version of the original Civil War, Captain America appears to die, and Bucky takes over the mantle as Cap (visit the guide). His days as Cap are amazing – great, layered storytelling. When Cap came back they shared the mantle for a while before Bucky was spun back to being Winter Soldier, at which point he began to sink back into obscurity – and he’s a white guy who stars in movies.

As with War Machine, he’s now a character Marvel needs to periodically kickstart into a new title or team only to watch him sink again.

Despite those concerns, check out the amazing list of Legacy Heroes Marvel is currently fielding:

Ant-Man: Raz Malhotra, a “South Asian” gay male (He’s only been used sparingly so far)

Ant-Man: Raz Malhotra, a “South Asian” gay male (He’s only been used sparingly so far)- Captain America: Sam Wilson, a black man (Yes, The Falcon is Cap! A character with a long history who is vastly the most-interesting Cap we’ve ever had)

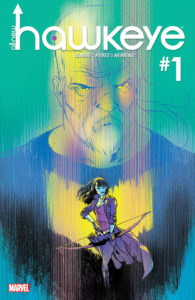

- Hawkeye: Kate Bishop, a young woman (around for a decade; rumored to be up for her own solo series; pretty much as much a perfect A student as Clint Barton is not)

- Hulk: Amadeus Cho, a Korean young man (a nearly decade-old supporting character who actually enjoys Hulking out!)

- Iron Man: Riri Williams, a black girl (debuted a few months ago)

- Moon Girl: Lunella Lafayette, a black pre-teen girl (made up freshly for her 2015 debut; this has some unfortunate implications since she is replacing a character who is literally a monkey)

- Ms Marvel: Kamala Khan, a Pakasani teen girl (created for her 2014 debut)

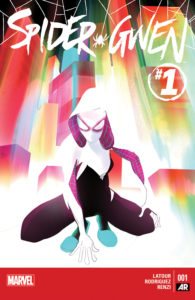

- Spider-Man: Miles Morales, a Hispanic and black young man (several years running character who was shipped in from an alternate universe where Peter Parker is dead – here is a strong critique of how Marvel markets his ethnicity but doesn’t write it), plus three Spider-Woman: Jessica Drew, a white woman and former Avenger, Silk, a Korean American woman, and Spider-Gwen, a white young woman.

- Star-Lord: Kitty Pryde, a Jewish young woman (This was short-lived, but Kitty Pryde is the best and I’m still counting it)

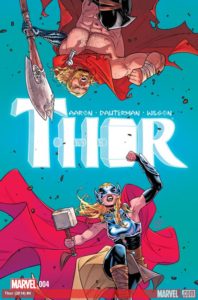

- Thor: Lady Thor, a white woman (a character who has been around longer than the majority of Marvel’s heroes but who is slowly dying – and Thor will feel badly about it)

- Wasp: Nadia Pym, a young woman (Wasp was at points the mantle of both a man and woman, so I still count this as a win)

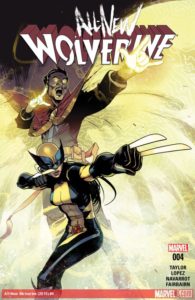

- Wolverine: Laura Kinney, a clone of Wolverine (around for about a decade, with several dozen prior leading-lady appearances to her credit)

What happens when all those white guys drop back in to reclaim their titles (other than Parker and Barton, who still bear theirs)? Will we still see these minority characters? Will audiences still buy them? Or, will they fade into obscurity only to pop up later to be killed off to make their white originators show some emotion?

Compare that to Black Panther and Storm, Marvel’s pair of most-visible black characters. They are no one’s replacement.

Of the original trio of Marvel Legacy Heroes – She-Hulk, Spider-Woman, and War Machine – two are not faring well right now, and a third is in the midst of a plot that’s – at best – a bit of a problem that could have been better off with a female co-writer.

It’s good that we have all these characters, but we have not seen that Marvel knows how to use them sustainably and responsibly once the novelty wears off. It takes stewardship and good storytelling to avoid that fate. Writers and editors need to care and keep caring.

We should still celebrate Riri Williams, but it must be a cautious celebration that stands ready to hold Marvel accountable for their treatment of her one, five, or ten years from now.

![]()

2. When will the diversity of Marvel’s creators match the diversity of their books?

I am not a believer in the idea that you must be the gender or color of your character to write them well.

I am not a believer in the idea that you must be the gender or color of your character to write them well.

I’m also a white dude, so I lob that sentence from a position of privilege

Yes, many good stories about women and black and queer characters have been told by straight white men. Many white guys have powerful stories they want to tell with those characters! But, how many better stories might we have missed out on from creators who match the diversity of the characters? What nuances of identity have we not seen on the page because white writers without the matching experiences simply do not have access to them?

In a world of novels, it’s easier to say, “There’s room at the table for everyone. Everyone can publish! Buy this book by a white guy AND this book by a queer black woman, you’ll love them both!” However, big-label comic books are a fixed-sum game. Marvel releases a huge but still finite amount of books each month. The four current ongoings that Brian Bendis typically writes are the only means we have of accessing a number of Marvel’s diverse characters, which means we may never see a take on them by non-ciswhitemale writer while he has the reigns.

So, while I think any person can and should write any character, a do think that a company with a diverse set of intellectual property owes it to their property to have a diverse group of creators advancing it. It doesn’t have to be one to one demographic match – we don’t need a hispanic and black writer to write Mile Morales; Ta-Nehisi Coates doesn’t need to be African royalty to pen Black Panther. But, different voices should be in the mix.

There is a good approach to making this happen in comics, which is one of collaboration and mentorship. As far back as Ms. Marvel #1 in 1977, Archie Goodwin worked with (and credited) his wife Carla for her consultation on the decidedly feminist hero.

When Kieron Gillen recently took on writing Angela for Marvel, he did so with an entire team of female creators including co-writer Marguerite Bennett. Though she had written for DC previously, that was Bennett’s second issue for Marvel, and since then she has gone on to write Angela solo even though Gillen stepped away.

When Kieron Gillen recently took on writing Angela for Marvel, he did so with an entire team of female creators including co-writer Marguerite Bennett. Though she had written for DC previously, that was Bennett’s second issue for Marvel, and since then she has gone on to write Angela solo even though Gillen stepped away.

Marvel’s white writers do this mentorship and handoff for each other all the time – I just recapped how Bendis did it with now-superstar Jonathan Hickman for my Secret Warriors page, and both Kelly Sue DeConnick and G. Willow Wilson did it for my personal fav Kelly Thompson in 2015. Even if editors still hold final approval, there’s clearly an existing path to tread.

Will Bendis take the opportunity to mentor a black writer, or a female writer, or a black female writer into the fold of Marvel as he introduces Riri Williams?

Sticking with gender for a moment (which is easier to parse quickly than color or sexual orientation), Marvel’s line-up is impressively comprised about half books lead by a solo female or that are teams that are at least half women. Yet, they have scant few female creators on their books – and, just one I can think of on a non-female-lead book (writer Becky Cloonan on Punisher).

You can do the mental math: there are <X female creators on X female books, and only Y female creators on other books. That means that while Marvel is finally leading the way on gender diversity in their casts, they’re still lagging behind the scenes. The data on creators of color or those who are queer tells a worse story.

As Uncle Ben says, with great power comes great responsibility. It’s not easy for all these white male creators to write an every-growing non-white cast of heroes well no matter how pure-of-heart and good-of-intentions they are. In some cases, they simply might not be equipped with the perspectives that will make the story ring true.

Conversely, if the diversity of creators improves across all books, the diversity of perspectives in the books – both in writing and art – will likely do so, too.

Which brings me to my final point…

![]()

3. How will this black girl be portrayed? (Will it be as a girl?)

I cannot lay claim to this critique – it’s one I saw leveled by a number of black woman critics today in the flurry of Twitter and I’m very happy to have learned from their voices.

I cannot lay claim to this critique – it’s one I saw leveled by a number of black woman critics today in the flurry of Twitter and I’m very happy to have learned from their voices.

Look at that illustration at the top of this page introducing Riri Williams as Iron Man. Then, look at the all of the other covers from early in the lives of female Legacy Heroes included with this post. Note that only one of those women is older than 18 years in story – Lady Thor.

Did you notice something? Only one is deliberately presented as statuesque. Only one has her breasts accented in the art. Only one has her midriff bared. It’s the black woman. And, I tried to choose the covers from all of their series that were the most sexualized I could get. But, they aren’t very, are they?

(Notably, Spider-Gwen’s male creator Jason Latour freaked out when other artists drew his teenaged while female hero with prominent breasts and a sexualized figure. It turned into a massive internet shouting match.)

Here’s the thing – older white guy me didn’t even notice this aspect of the Riri’s image until others pointed it out to me. I thought for comic art it was still relatively tame. Yet, I am aware that young black women are sexualized in the media and consistently presented as more mature than their age. I know that part of the narrative of the danger of young black males is describing their physiques as advanced or “monstrous” or, if you’re trying to find a reason you shot and killed a boy, “like a demon.”

[I hope to add some links to that paragraph later as supporting evidence, but the things I’m mentioning are common enough tropes that I don’t feel like I have to prove they are real to make my point. Further reading: Hypersexualization: The Black Female Body is a great and brief presentation; Michael Brown Wasn’t a Superhuman Demon (but Darren Wilson’s racial prejudice told him otherwise) helps to define implicit bias and shows this isn’t purely about black girls, but all young black bodies; Sex Stereotypes of African Americans Have Long History helps negate the “it’s just a comic book, dude” argument; and, Mainstream Hip Hop Culture’s Commodification of Black Female Sexuality addresses how this issue is self-perpetuating]

No one is saying Riri Williams must be drawn as pudgy or covering all of her skin, nor must she be called Iron Girl, or Iron Maiden, or Iron Lady. In portraying this 15-year-old – even as we are shown her advanced intellect – are we being reminded she’s still a girl?

Honestly, we don’t know. We have a single cover image and zero story to go with it. In this singular image chosen specifically for the bomb blast impact of its accompanying news on comics fandom, the celebration of Williams’ blackness with dark skin and afro hair is inseparable from her sexualization.

Honestly, we don’t know. We have a single cover image and zero story to go with it. In this singular image chosen specifically for the bomb blast impact of its accompanying news on comics fandom, the celebration of Williams’ blackness with dark skin and afro hair is inseparable from her sexualization.

![]()

In the title of this post I ask if a black female Iron Man is a good thing. I still think the answer remains unequivocally: yes.

Good things can still be problematic. Good things can still become better things

Let’s remember that the goal throughout our lives – in fiction, at work, and at home – ought not to be tokenism but inclusion. Marvel will have succeeded in improving representation in their heroes not when we can tick off a long series of boxes, but when that range diversity is represented in persistent inclusion of those characters in the stories that matter – and, yes, sometimes those characters will get hurt, make mistakes, or even die in those stories.

To get to that point, we don’t just need minority Legacy Heroes – we need heroes that really matter.

![]()

I’d love to hear your thoughts on this, but let me make one thing clear: any comments along the lines of “I don’t like this quota filling” or “these aren’t real heroes” or “Marvel is ruining this character for me” will probably be deleted. It’s my blog, so you don’t have freedom of speech here. The general idea that inclusion and representation are positive is not up for debate. Got it?

[…] means all representation is good representation, like Riri Williams as Iron Man, but having a diverse cast just step one of a truly representative fictional world. Step two is […]