[Patreon-Nov16-Post-Bug][/Patreon-Nov16-Post-Bug]It’s the fourth installment of my “From The Beginning” read of Dr. Seuss’s entire bibliography. Last week I covered the surprisingly awesome The King’s Stilts.

[Patreon-Nov16-Post-Bug][/Patreon-Nov16-Post-Bug]It’s the fourth installment of my “From The Beginning” read of Dr. Seuss’s entire bibliography. Last week I covered the surprisingly awesome The King’s Stilts.

After that lengthy prose story with a clear message, Dr. Seuss returned with the a rhyming book that both looks and feels like the Seuss we all know and love – Horton Hatches the Egg. Yes, it’s the same Horton who would later hear a whoo. Between the meter and the silly animals, it was liked well enough by the toddler but we were quickly back to The King’s Stilts afterwards … and I think I know why.

Horton Hatches the Egg (1940) – Dr. Seuss

Reading Time: 8-12 minutes

Gender Diversity: Horton and the hunters are male; the lazy, shrill bird, Mayzie, is female. Animals are otherwise agender; there are women in a circus crowd.

Ethnic Diversity: None

Challenging Language: kinks, fluttered, tenderly, lightninged, anew

Themes to Discuss: parental responsibility, keeping your word, teasing and being different, hunting and animals used for entertainment, genetics, nature vs. nurture

You probably know Horton the elephant because he heard a Who fourteen years after this book was published, but this was his first appearance – and also Seuss’s first time anthropomorphizing an animal as a main character in one of his books.

Horton Hatches the Egg is a frivolous tale about responsibility and keeping your word that’s a fun read with little ones but lacks some of the narrative hooks that make other Seuss books great.

Horton isn’t the first animal we meet in this story. Instead, it’s Mayzie, a feckless bird who is bored with incubating her egg. While she isn’t quite ready to let it die of exposure, she’ll accept any substitute for her own tail feathers to keep it warm – including the massive hindquarters of Horton the Elephant.

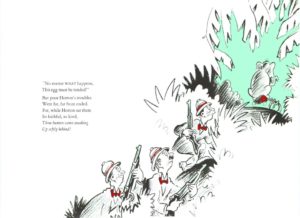

The good-natured Horton is happy to help, and once Mayzie flees the scene he insists to maintain his sworn duty because he meant what he said and he said what he meant, 100% person. That’s true ven when he’s teased by the other animals and menaced by hunters. Luckily, the hunters realize an egg-sitting elephant is likely more valuable than his ivory and ship him off to America, where he can be gawked at in a circus.

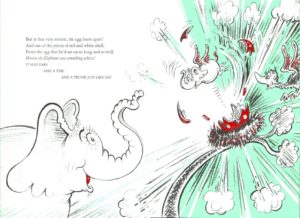

When Horton’s show happens to make its way to where Mayzie is permanently vacationing in Palm Beach she decides she might liked to have her egg back. Just as she’s ready to get into a pecking match with Horton over it, the egg bursts upon to reveal a tiny flying elephant – apparently Horton’s dedication to the egg’s inhabitant was so powerful that it wound up being as much his as it was Mayzie’s.

When Horton’s show happens to make its way to where Mayzie is permanently vacationing in Palm Beach she decides she might liked to have her egg back. Just as she’s ready to get into a pecking match with Horton over it, the egg bursts upon to reveal a tiny flying elephant – apparently Horton’s dedication to the egg’s inhabitant was so powerful that it wound up being as much his as it was Mayzie’s.

After two lengthy books of prose, I was surprised when Horton turned out to be in Seuss’s famous and familiar style of meter (his usual go-to is anapestic tetrameter, but my wife the word nerd says this is closer to dactylic). It’s much snappier than Mulberry Street, with more wordplay and internal rhymes. It’s also more engaging, since Horton is directly involved in the action whereas Marco was just imagining it.

Despite the comforting familiarity of Seuss’s rhyming, Horton’s message is not as clear-cut as in later Seuss books, and certainly not as much as the fable of The King’s Stilts. There’s Horton’s laudable stick-to-it-ness, but it pays off in him hatching an offspring that he didn’t necessarily want in the first place. The hunters refrain from gunning down something unique, which I suppose is a positive message.

Past that, Horton as our protagonist displays an interesting kind of agency here – effectively, the choice to be stubborn or to do something by doing nothing. While that’s a positive within the story since he’s protecting the egg, I can sometimes catch my toddler glazing on this tale as we read page after page of things happening to Horton who never really changes his message.

Furthermore, for young readers, the bird shirking her eggs and then later so desperately wanting it back is going to lead to some confusion. Because I tend to answer “Why?” questions with science, this lead to a discussion of biological imperatives versus wanting to do something. If your toddler chats don’t get that deep, expect the question to linger.

It’s tempting to read modern intent into Dr. Seuss’s stories. This one has plenty of potential hooks to hang your interpretations. The bird could be people on state assistance and Horton a leftist nanny-state government who insists on providing. It could be a message about nature versus nature or a comment on white families adopting children of color. The hunters could be forces of colonization or even the media, so eager to put a thing on display without understanding the why behind it. Heck, it could even be an allegory about the debate around abortion!

You can give in to the temptation to read your meaning onto Horton, but don’t make the mistake of assuming Seuss’s position on any of these matters. Part of what makes an allegory great is its universality, and even this Dr. Seuss book that didn’t age as well as its neighbors has that in spades.

[…] Today is the fifth installment of my “From The Beginning” read of Dr. Seuss’s entire bibliography. Last week I reviewed the slightly odd, lesser-known Horton book Horton Hatches the Egg. […]