Lately, I trust journalists less than ever before. Or, maybe I trust them, but I don’t trust the stories they’re telling.

Last week during the gun control filibuster on the Senate floor I compiled the names and demographic information from all the participating Senators, and my friend Lauren created an interactive infographic with the information. I did not read a single media story that named all of the participants after the fact.

I know this is a theme in conservative American politics right now – the bias of the mass media. I’m not talking about bias. I’m talking about facts.

The past few weeks have been full of big new stories nationally (Orlando and gun control) and locally (sugary drink tax and the DNC), and the biggest of those stories have been missing so many facts. They’re all headlines and quick hits. Hot takes with no depth. No quoting from primary sources. Lots of people coming away with incomplete ideas and parroting them as reality.

Those same weeks have also been full of truth. I become deeply invested in last week’s filibuster from the floor of the Senate and did not consume a single pundit’s take on it. I watched it live and was my own pundit. Yesterday’s sit-in in the House circumvented pundits even further – it couldn’t even be broadcast by networks because the House was out of session and cameras were off, so representatives broadcast it directly to the public via Periscope, cutting all all possible middlemen.

Of course, the next day journalism swept in – but, as a first-hand witness to the events in question, I found the subsequent coverage lacking. Where were the names of the participants, the lengths of time they spoke, the information they shared? I put more information together about the filibuster with data visualization from my friend Lauren than I saw from any news site!

I don’t trust journalists or I don’t trust the stories they tell, but I can hardly blame them. After all, I have a journalism degree and I never set foot into that field. I went CorpComm because I wanted job security and a standard of living, and that was before online outlets were effectively subsidizing their print editions and running on pay-per-click ad units. But I still believe journalism should represent unfiltered truth with a neutral point of view, unless it professes itself as opinion. I had a lot to say about the filibuster, but none of it made its way into the data.

What if journalists didn’t have to worry about the funding and the hits, and could focus on terrific journalism? There are some outlets today that fit the bill, and I don’t think it’s coincidence they produce some of the most thorough reporting. I know it’s hard to picture state-run journalism, because so often it’s journalists who expose the flaws in the state, but that’s one version of what I’m talking about. Instead of asking journalists to make personal sacrifices to do what they love and write for maximum eyeballs, imagine a minimum number of reporters guaranteed on each beat, with job security, fair pay, and a retirement plan.

Do you think the journalism would get better or worse? Does it take sacrifice to want to dig as deep as journalists dig? Or, would the skill and commitment increase?

![]()

The Private Eye

The Private Eye

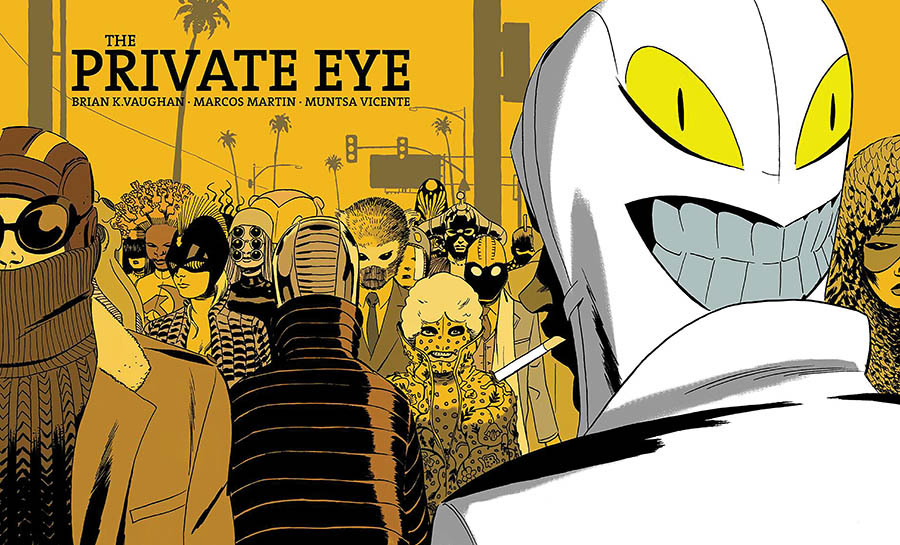

The Private Eye collects the 10 chapters of a complete web comic story by Brian K. Vaughan, Marcos Martin, and Muntsa Vicente.

Tweet-sized Review: The Private Eye finds Vaughan & Martin a bit too clever for their own good; I liked the world better than the story

CK Says: Consider it.

The Private Eye is a much more interesting world than it is an interesting story – and, it’s a pretty decent story.

Private Eye is an Eisner and Harvey Award Winning comic story conceptualized by Brian K. Vaughan and created in collaboration with Marcos Martin and his wife, colorist Muntsa Vicente. It was initially released beginning in March 2013 as a web-only comic via Panel Syndicate, with its 10 chapters released across 24 months. Each chapter was available as a DRM-free as a pay-what-you-will download.

You can still purchase it that way, or you can opt for a gorgeous $50 hardcover version released in December that includes the complete Vaughan/Martin email chain conceptualizing the story and their method of release (complete with fretting over what to call the website and how to make a profit from it).

The story of Private Eye depicts an America where the press has taken over peacekeeping for the police thanks to a landmark omni-leak of every possible piece of data. The event, called “The Cloudburst,” exposed everyone’s online information to everyone else. It wasn’t the leaked account balances or private nudes that did everyone in, but the search histories. It turns out that was as close as you could come to knowing what was going on inside someone else’s head – their deepest fears and desires. A lot of those heads were pretty dark places.

Information is power in this new world, which is why detectives have been replaced with reporters. No one wants to commit their real identity to any action – not buying bread and milk, and certainly not committing a crime, but not even going on a date. Every regular citizen tries to deprive their peers of any personal knowledge to protect the sanctity of their core identity. It’s a world full of masks and pseudonyms, where the worst thing you could do is let slip a detail from your real life while out living your best life.

Information is power in this new world, which is why detectives have been replaced with reporters. No one wants to commit their real identity to any action – not buying bread and milk, and certainly not committing a crime, but not even going on a date. Every regular citizen tries to deprive their peers of any personal knowledge to protect the sanctity of their core identity. It’s a world full of masks and pseudonyms, where the worst thing you could do is let slip a detail from your real life while out living your best life.

If that sounds at all fascinating to you, know that I am hardly doing it justice. There are so many nuances in the world, and not just as its revealed from Vaughan’s script. Marcos Martin does career-defining work here, filling in every corner of the page with little details of life in this post-identity world. His figures remind me of Steve Ditko in their Silver Era simplicity, an impression only abetted by the bright, solid-color palette employed by Vicente.

With the sunny depiction of the world, it’s hard to decide if this is Utopia or Dystopia. The information event horizon ruined relationships and lives, but years later everyone looks bright and happy as they are free to do whatever they want in a world of mutually assured privacy without an omnipresent internet to link them together.

(Also, apropos of nothing, I take note when a book includes equal-opportunity nudity that shows as many men below the belt as women without shirts, because all people are nude sometimes. This one does.)

By the way, I haven’t really spoiled a thing yet – all of this is background information from the first one or two chapters of the book.

Vaughan pairs this advanced concept with the simplest of gumshoe stories – a dead dame, a vengeful associate, and a bigger conspiracy at play. With the police state shifted to the fourth estate, one thing that didn’t change so much was private investigators. They’ve always been half cop, half journo, after all. Now instead of being despised as hired snoopers, they’re thought of as paparazzi – tattling rogue reporters out to uncover dirt. Except, in this world, that dirt isn’t tabloid fodder – it’s potential control over someone’s entire life.

Vaughan pairs this advanced concept with the simplest of gumshoe stories – a dead dame, a vengeful associate, and a bigger conspiracy at play. With the police state shifted to the fourth estate, one thing that didn’t change so much was private investigators. They’ve always been half cop, half journo, after all. Now instead of being despised as hired snoopers, they’re thought of as paparazzi – tattling rogue reporters out to uncover dirt. Except, in this world, that dirt isn’t tabloid fodder – it’s potential control over someone’s entire life.

As Vaughan unspools more story the scope of the mystery gets bigger as do the consequences, but I found it increasingly less interesting. I went from turning pages in Chapter 2 as if I was gasping for air to idly reading a few pages at a time of an action-packed conclusion full with characters of whom I’d grown bored.

It felt as though Private Eye was building up to a bigger mystery than it could ultimately deliver. What could be more mysterious than the world Vaughan had built? Nothing could top it!

Yet, you cannot accuse Vaughan of not sticking the landing. He’s is modern comics’ most deft author when it comes to creating beloved flawed characters and wrapping up his plots in a tidy bow. Every dropped hint wound up being relevant, and each character got their due. Maybe that means it’s my fault I didn’t love this one as much as it is the creators’. I think I got so swept up in Vaughan’s world and Martin’s pictures of it that I stopped caring about the people inside.

That can happen when everyone has a mask on all the time – you fall in love more with the concept of something than who they actually are.

[…] is the master creator of critical hits like Y: The Last Man, Ex Machina, Marvel’s Runaways, The Private Eye, and the still-running deeply personal space fantasy Saga, which is currently the biggest […]