Some people say “the art spoke to me,” but how often do they say, “the art made me speak”?

That’s how I felt about this week’s Black Panther & The Crew #1. My original plan was to give this new Ta-Nehisi Coates and Butch Guice Black Panther spinoff a quick read and a one paragraph review as part of keeping up with new Marvel titles.

I had no concept of how incredibly strong and thought-provoking of a comic it would be. In that regard, it feels of a piece with the nuanced first half of Netflix’s Luke Cage. The issue was so layered and powerful that words started spilling out of me before I could even finish reading. I was desperate to unpack all the thematic content. I couldn’t stop talking about it on Twitter, Facebook, or in the house with E.

As a result, this is as much as review as an attempt to identify and parse the several layers of identity and privilege in this story.

I’m a white man writing about a comic by a black writer about black women and their community. I make no pretense that I’ve got the right, best, or even relevant take on the issue – but, this comic moved me, and I think it’s a mistake not to write about art when it makes you speak.

I’m probably going to get some things wrong. I offer my apology in advance for that, and I’ll offer it again in specific if you point out where I am mistaken.

(I also offer this: It’s no one’s job to tell me how or why I’m wrong. If you are a black woman and you have a counterpoint to offer, please say so in a comment. You don’t have to offer your take for free. If you don’t have your own platform to publish on, I’ll get in touch to offer you a small stipend in exchange for featuring your commentary as a response here on the CK main page.)

One of the best parts of this comic is yet to come. No, not the appearances of Black Panther and Luke Cage. The even-numbered issues of The Crew will be scripted by poet Yona Harvey – one of the few times Storm has ever been written by a woman, and the first in-continuity arc with her written by a black woman. Ever.

![]()

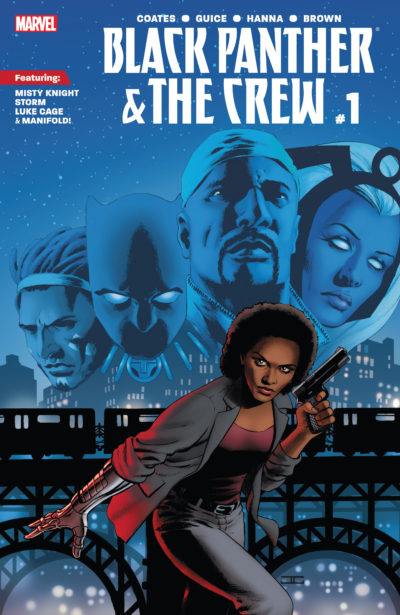

Black Panther & The Crew #1 (digital)

![]() Written by Ta-Nehisi Coates with pencils by Butch Guice, inks by Scott Hanna, color art by Dan Brown, and letters by VC’s Joe Sabino. Cover by John Cassaday with Laura Martin.

Written by Ta-Nehisi Coates with pencils by Butch Guice, inks by Scott Hanna, color art by Dan Brown, and letters by VC’s Joe Sabino. Cover by John Cassaday with Laura Martin.

Black Panther & The Crew #1 is dense with symbolism and thematic content, deliberately using its visual medium to create juxtapositions that would take many more pages to work through in a prose version of the story.

I haven’t yet read Black Panther by National Book Award winner and Atlantic correspondent Ta-Nehisi Coates, but the first issue of Black Panther & The Crew tells me I need to go back and catch up immediately.

I don’t know why this comic’s unwieldy title can’t just be “Misty Knight,” but I’m not going to look a gift horse in the mouth. Black Panther never appears. Coates uses Misty as a narrator to great effect, forcing the reader to pause to absorb the panel work as her narrated story frequently departs from the action we see in the art. Maybe the point-of-view character will rotate as the series progresses.

Misty’s story is really the story of Harlem, and of Ezra Keith. Keith is a former costumed crime fighter turned into a frequent anti-police protestor, though Misty has only put the connection together recently.

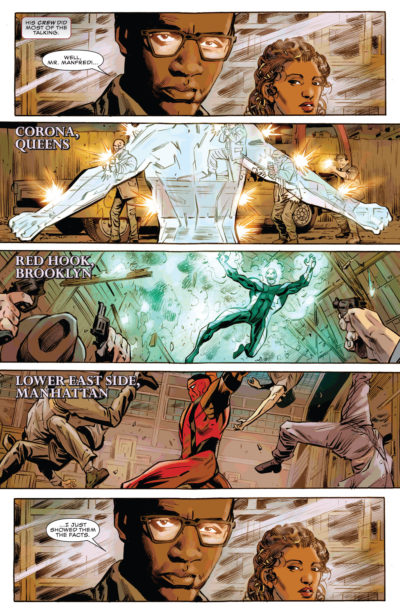

While Misty’s thoughts are on Keith’s case, Butch Guice’s artwork is elsewhere – first depicting a flashback of Keith leading his own Crew (called “The Crusade”) in 1957 and then showing Misty wading through a crowd of present day protestors as they clash with both local police and state-issued police-bots.

It’s not until Misty meets with Storm later in the issue that her thoughts and the images line up. It’s a powerful choice to snap the story fully into the present tense at that moment, even before Misty and Storm exchange their first words. It sets them up as peers, black women, community members, and heroes – but each with her own distinct stack of privilege acting as a filter.

Misty feels a connection to the community and their protests, but can’t help but keep them at a bionic arm’s length. When she sees something amiss in the death of an elderly citizen, her first instinct isn’t to protest or offer counsel.

Instead, she investigates.

The issue treads a careful line of whether that’s due to her skill as a detective or if it is her privilege as both police and superhero to enjoy a detachment from the immediacy of state-sanctioned violence against her community. The violence angers and disappoints her, but she can wade through a police line to visit the other side with impunity – at least, for now.

The comic is less equivocal on how that privilege is also double-edged sword. It’s hard for Misty to relate to her fellow officers, both as a member of the community and as a superhero. Misty has tried being a member of the community the police serve, a member of the police force, and someone stronger than them all, but no matter what role she takes on she endures a litany of micro-aggressions reminding her she’ll never really be just one of the cops again.

How much of that is down to the fact that she didn’t take her lumps when her arm was destroyed – instead accepting the aid of a superhero to reject becoming a disabled person? Not all other officers get that choice.

(This lead me to a discussion with my wife, a woman of color with seniority in the tech industry. In some situations she has not experienced the discrimination other women face in tech. Other times she’s unaware of her lack of privilege until she has someone else’s experience to compare to her own. In each case, she has no way to know why she was singled out. Her privileges (and lack thereof) are unique and mutable, and they are mitigated by her ability to code switch for different social situations.)

An unusually casual Ororo Munroe – usually known as Storm, but here called “Blue” – is seemingly more accepted than Misty in the wake of a community member’s death.

Ororo is at home in the Harlem neighborhood of her African-American father, where she lived prior to moving with her parents to Cairo as a child. She easily code-switches from hero to community member, even with her nickname of “Blue” calling out one of her strikingly different physical features.

(Note that Ororo wears glasses to disguise her blue eyes. Also, her shock of white hair remains wrapped in a scarf while she acts as a community member. She has visually minimized the preternatural difference of her biology while the community grants her access as a peer rather than a hero.

By contrast, Misty wears her traditional puff of natural hair, but she also keeps her shirt sleeves cuffed up to expose her bionic arm throughout the issue. She proudly displays the mark of her preternatural ability as a badge, despite not visibly displaying her actual police badge.

Butch Guice has always been a sketchy artist, and part of his charm are his rough edges. He seems to be having some trouble with a few aspects of this black cast, including Misty’s should-be-beautiful hair. I saw a number of black women on Twitter calling out the lumpiness of Misty’s afro – a particular affront after seeing Simone Missick’s divine twist-out version of Misty’s hair on Luke Cage.)

We get no details of Storm’s connection to the family of the deceased man. Yet, it’s obvious she’s acting as both a confidant and advocate to them in a way that Misty cannot access.

Coates uses the two leading women to make commentary on privilege, but deftly assigns the bulk of his most incisive social commentary to elements of the fantastic.

Superheroes were responsible for ejecting drugs from their community under the radar of the law in the 1950s. Back then, they were simply exceptional members of the Harlem community. Today those exceptional members have been whisked away to the X-Men, the Avengers, and the Fearless Defenders, leaving only old heroes like Ezra Keith to take a stand in the community.

(Is this meant to mirror the flight of successful members of a community to more upscale/gentrified neighborhoods rather than reinvesting in the community that supported them?)

That stand is now as much against criminal elements as it is against law enforcement. That’s not just the NYPD. The duty of maintaining curfew and other broken-windows style policing falls to a squad of overly-aggressive law enforcement robots.

Coates knows we want to see our pair of heroes strike a blow against the perceived police state. He’s also wise enough to avoid making that a direct battle between human beings, which comes with unavoidable comparisons to our present day reality. We don’t need automatons to create police violence against black bodies in the real world, and we also don’t have any superheroes to protect them.

Coates and Guice subtly emphasize the looming presence of the police-bots. They are shot from below to imply them looking down on us as the reader, and later hover just above Misty and Ororo. How satisfying it will be for us to see the modern heroes and the automatons pitted against each other, all in the name of old hero Ezra!

Yet, to access that heroism, we first have to bear witness to the bodies of two black women struck down by the police. We see Ororo, a literal goddess, brought to her knees and Misty, an unbreakable cop, wincing in pain.

I did not read that simply as a “they shot first” justification for the impending superhero beatdown, but a reminder that in the real world the story ends after the police escalate. There’s no counter-punch. The page layout is deliberate in containing all of Ororo’s punishment on a page where she has no chance to respond. It’s gut-wrenching. I feel sick reading it despite knowing that her retaliation follows on the next page.

The two women both respond in kind, but their response continues to bear the weight of their privilege. Misty is a member of the same police force as these inhuman enforcers. She strikes back only at the robots who struck them first, buying time for Ororo to recover.

Ororo has no such allegiance. When she arises, it is with her glasses removed and her hair unwrapped. Here, she is Storm – and she will leave no aggressor standing in the wake of her onslaught. It’s a singularly iconic super-hero moment and a counter-weight to the super-powered flashback that opens the issue.

I love it so much that I won’t excerpt it here as fair use.

You should buy the comic so you can see it for yourself.

Black Panther & The Crew #1 is available digitally right now on Amazon! You can also pre-order the trade paperback containing issues #1-6. For more Black Panther, see my complete guide to his every appearance.