Should certain stories be off-limits?

Consider if you have ever watched a movie or read a book where you felt a certain story beat was in particularly poor taste. Perhaps it should have been avoided altogether.

Does that mean no author ought to attempt it again?

I find that to be a difficult question to answer. Personally, I loathe plots where someone who is abused comes to trust or love their abuser. I think that plot relies on outdated trope about the internalization of cruelty as a form of affection.

I find that to be a difficult question to answer. Personally, I loathe plots where someone who is abused comes to trust or love their abuser. I think that plot relies on outdated trope about the internalization of cruelty as a form of affection.

Creators ought to be wise enough to steer clear of that plot in most instances, but I don’t think it should be outlawed. I can imagine a time when you might want to steer into that curve – not to be divisive or subversive, but to say something about your flawed characters. But it’s not a curve that should be mistaken for terrific character development.

There are other plot points that result in me getting up and walking away from the book or TV show I had been consuming a moment prior, whether they be personally triggering, advocating harmful behavior, racist, sexist, homo- or trans- phobic, or just plain dumb.

I don’t think any of them ought to be off-limits. Writing a bad story is entirely up to you. I won’t stand in your way, nor should anyone else.

I do think some portrayals of plots ought to be off-limits – not by rule, but in practice – because they irresponsibly normalize dangerous behavior without context. People are now savvy enough to understand how to reject dangerous stories at face value, but not all consumers understand how to reject dangerous framing of concepts.

This can be insidious. I cannot watch a TV show or a movie that portrays sexual violence with a romanticized gaze. If you are going to make the choice to depict a sexual assault, it should be viscerally disturbing to the viewer. Their gut should twist. Not because you are editorializing about sexual assault, but because that’s what sexual assault is.

It is the difference between my ability to endlessly re-watch Watchmen despite it disturbing rape scene and my inability to make it through the sexual violence in the first season of Game of Thrones. One was viscerally disturbing. The other one kind of wanted to be sexy. Yet, many people causally watch both the former and the latter.

(You can substitute another topic for sexual violence, if you prefer.

This week, the depiction of death by suicide has become a hot topic due to its portrayal on 13 Reasons Why.

Romanticized portrayals of violence or self-harm erode a viewer’s ability to discern the objective truth of an event in reality. The fictionalized version takes over – whether that’s the seductive ease of ignoring informed consent or the glamorization of suicide.

It’s not that people object to suicide as thematic content. It’s the way it was framed.

Last week, news broke that a new BBC show depicting the UK Black Panther movement was centering a South Asian woman as it primary protagonist rather than a black woman. Regardless of the dubious historical accuracy of such a choice, choosing to cast non-black woman as central to a black civil rights movement erases black women from their own history. We saw a similar act of erasure of trans women of color in the movie Stonewall.

It’s not that people object to non-black characters appearing in historic civil rights narratives. Is the lack of portrayal of black woman.)

Having established my particular dichotomy of offensive story vs. irresponsible portrayal, now let me lay this one on you:

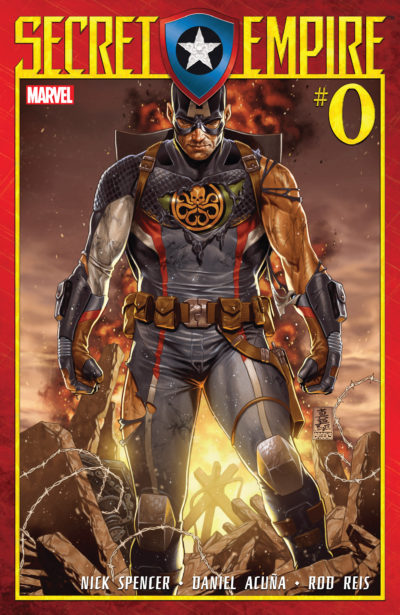

Last year, Marvel Comics and author Nick Spencer made Steve Rogers – the original Captain America – a Nazi.

(Let’s not split hairs – Hydra is a Nazi organization whose ideals have been slightly sanitized for comics. More on that in a moment.)

He isn’t pretending. He wasn’t brain-washed. Hydra used the Cosmic Cube to retroactively change Steve Rogers from American boy with a heart of gold to Nazi-sympathizing double-agent.

On one hand, I don’t think Cap being altered to be a truly vile villain should be off-limits as a story. I don’t think making him the symbol of everything he has fought against ought to be immediately rejected.

On the other hand, Nazis.

Right here, right now, at this point in history we are seeing the danger of the trivialization of Nazis as token villains detached from the explicit horrors they perpetrated. As a collective culture we have begun to believe they are the stock evil characters, cardboard cut-out bad guys to knock down. We have become inured to them existing in the real world beside us, or as advisors to the leaders of our country.

Or, put more succinctly:

In other words, does the inclusion of Nazi figures or iconography constructively examine and interpret the social and political era of WWII in Germany, especially in its sensitivity to the Holocaust, or does it merely utilize the Nazi figure for its grotesque fascination and entertainment value? …

… These authors and artists present their comics as fiction, yet the texts’ focus on supernatural imagery mythifies and trivializes historical Nazism, and by implication threatens to dismiss the significance of

WWII and the Holocaust.Withorn, Tessa, “Holocaust etiquette, myth, and metanarrative : representations of Nazism in contemporary comics.” (2015). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 28.

Retrieved from http://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors/28(I’m still working through this thesis; if you are interested in this sort of thing, it’s incredible.)

Through repeated exposure to these sorts of portrayals of Nazism, we erode our barometer of the true evil of Nazi acts committing during World War II. It’s how we can, over time, arrive at statements that begin with a phrase like, “Not even Hitler…”

The historical trauma of the Holocaust has been repeatedly minimized until it is an easy-to-wield yardstick for measuring increasingly shallow depths of horror, and Nazis are potentially-inert, frequently-bumbling villains who don’t need to be proactively punched.

Thus, while it is fine for Captain America to be a Nazi (though that might be a bad story), the portrayal of him acting out a trivially grotesque form of Nazism codified as “Hydra” minimizes the actual truth of Nazis murdering millions of people. Even the bumbling ones.

You are being asked to either forget the Holocaust in your digestion of the story or to recall the Holocaust and still enjoy digesting the story without wanting to vomit it back up.

Secret Empire #0 is the prologue to the payoff of the “Steve Rogers as inoffensive Nazi” plot that began a year ago. I have read none of that plot, although hearing the reaction to it has been unavoidable in my social media sphere. Captain America is a beloved symbol of America and freedom and Marvel and Spencer have the tremendous bad taste and/or misfortune to recast him as a Nazi – not just a brainwashed Nazi, but a reality-altered permanent Nazi – at the same time actual Nazis have infested our actual government.

I think it’s Marvel who has the bad taste and Spencer who has the misfortune.

Marvel is talking about advertising Secret Empire via taking over stores and websites with Hydra propaganda. Clearly they learned nothing from the public response to Man In The High Castle doing the same on the subways of New York. They’ve not only completely missed the Holocaust Etiquette memo, they’ve also failed to read the mood of America at the moment.

Spencer, generally an incisive and trope-crushing writer, had the misfortune to pitch this plot (likely in mid-2015) at the best and worst possible time for its real world resonance. I won’t hold his plot against him purely for its poor timing, but I might still reject his portrayals.

I won’t hold his plot against him purely for its poor timing, but I might still reject his portrayals.

I’m going to review Secret Empire #0 cold, knowing nothing about Spencer’s current Cap run save for browsing a few issues of Sam Wilson as Captain America (because I love him – he is my Captain America). I cannot yet say if Spencer has also been irresponsible in his depiction of Cap’s Hydra-as-Nazism, though I’ll be watching for that in issue #0.

Then, in the coming weeks, I will catch up on both Sam Wilson and Steve Rogers as Captain America prior to reading Secret Empire #1 to see my opinion is changed by the full context of Spencer’s story.

Secret Empire (2017) #0

![]() Written by Nick Spencer with art by Rod Reis (prologue) and Daniel Acuna (main story), and letters by Travis Lanham.

Written by Nick Spencer with art by Rod Reis (prologue) and Daniel Acuna (main story), and letters by Travis Lanham.

Secret Empire #0 is a dire prelude meant to paint Marvel’s heroes (and the entire Earth, along with them) into the worst possible corner from which they can fight their way out for the nine-issue run of this event series.

It succeeds in that goal, maybe even topping similar high stakes conflicts set up in prior events like Infinity and Fear Itself. That success comes with the cost of making Marvel’s most tried-and-true hero into a villain so intensely despicable that this issue barely has a chance to hint at his evil.

I’m not sure the high stakes of the story were worth that.

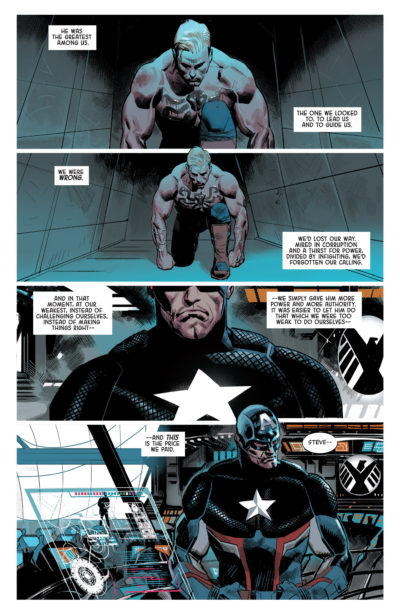

If you haven’t been keeping up with Captain America, this book will be a gut punch from page one. Captain America bows and hails Hydra in the fourth panel. It’s not a trick. This is the story – that Cap has been affiliated with Hydra even before his icy deep-six towards the end of WWII.

That’s hard to swallow on several levels. Cap as a permanent, devoted member of Hydra simply doesn’t make sense after all he’s been through without him ever defecting to help out his brethren in a pinch – particularly during Fear Itself.

Spencer deflates that critique before you can fully articulate it. The regular, lovable flavor of Steve Rogers was retroactively replaced with a Hydra version of himself at the exact moment he could become pivotal in a 70-year plot for world domination. There’s no need to reconcile a secretly Nazi Captain America with his over 70 years of comic stories.

Part of the power of Spencer’s concept here is how utterly, transparently dumb it is. It’s, like, Wayne’s World dream sequence levels of stupid, a pastiche of hair-brained 60s-era comics plot devices. The bad guys earnestly believe (or, at least, claim to believe, for Steve’s sake) that they are the good guys as they use the trope of sending an agent through time to a future he doesn’t entirely recognize to be their sleeper.

It’s entirely ridiculous that Hydra would set up this scenario with the power of the Cosmic Cube at their disposal. It’s equally ridiculous that Hydra would claim that the Allies used the Cosmic Cube to steal a win in World War II from the jaws of defeat in a sort of reverse Man In the High Castle while they still left intact horrifying events like The Holocaust or the dropping of a pair of atomic bombs on Japan.

But, Hydra is that dumb, and so is this plot. Despite its mature themes, this is a comic book grounded in the foolishness of classic comic books rather than the realism of modern ones.

Spencer blends in a slurry of mysticism and downplays Hydra’s organizational aims in this sequence to divorce his concept from actual WWI nazism, but you can’t help but see the Red Skull’s face stare back at you from the magical propaganda display. Red Skull is the most iconic representative of Nazism and white supremacy in comics fiction. Skirting his legacy to re-cast Hydra as generic bad guys begs the question of why we couldn’t have this same plot with the equally hapless A.I.M., or some other group of non-Nazi villains.

Rod Reis’s pencils on the prologue are incredible. I was so distracted by his artwork that I had trouble reading the word balloons my first time through the issue. His desaturated colors and white highlights recall Dean White coloring Jerome Opena on Uncanny X-Force. It’s hard to believe just one human being is handling both the line art and color art on this section. I cannot possibly overstate how cool it looks.

From there we flash to the present day.

Earth’s heroes are fighting a war on three fronts. It’s hard to tell if their fights in space, on Earth, and against another helicarrier are made up from whole cloth here or if they have precedents in other books. Regardless: they are effective. Many prior events have tried and failed to sell the narrative heft of a multi-front war. They often focus on the scope of the conflict and not the people. Jonathan Hickman, in particular, loved to focus on the sheer size of each challenge, but his Infinity never truly sold the urgency of pitched battle occurring on Earth.

Spencer is much more interested in the people inside of the sizable challenge. We get brief, personal, painful moments with characters like Captain Marvel, Jessica Jones, and Riri Williams as Iron Man. As Spencer (and Cap) twists the knife on Earth’s heroes, you’ll find yourself really feeling for these three women, along with Sharon Carter – who has a front row seat for Steve Rogers’ betrayal.

That’s right – all the leading heroes in this book are women. Every damn one.

When it comes to superhero comics, inclusion often comes hand-in-hand with peril. That means that a cast of leading ladies yields scenes of a young, female Quasar being swallowed by a giant space phallus and of Jessica Jones nearly recreating the deadly opening scene of the original Civil War with Nitro.

I think Spencer does a better, more authentic job of inclusion than Brian Bendis did in Civil War II, an where inclusion equalled peril in the opening chapter. Women are not only in peril here – they also share equally in the big, heroic moments. When the earthbound heroes need a relief squad to save the day, it is fronted by Rogue striking a power pose in mid-air. A splash page of the “heavy hitters” gathered in space is dominated by amazing female characters.

Across all three fronts of battle, artist Daniel Acuna has pumped up the drama of his work. He’s given away some of his typical subtlety in exchange for delivering bigger superhero moments.

It’s a good look on Acuna, who is also coloring himself here. His art can look a bit drab when he skimps on strong ink lines and highlights. With those elements in place, his work has more superhero zip than usual.

If his self-coloring has a weakness it is in faces. Too often Acuna contrasts different planes on a face with a slash of rose color against peach-colored flesh. It gives his faces an unpleasant heaviness that is hard to ignore.

Spencer is also wrestling with heaviness. His weight is the the narration of an unseen narrator speaking from the future. The heaviness isn’t providing us with an appropriate amount narrative dread. It’s more like “too much ink on the page.” These foreboding, disembodied comments are awkwardly scripted and too plentiful. Skipping past every second or third one greatly improves the issue.

Between the meaty faces and the overbearing narration this book can get downright lugubrious at points, especially when Cap is on panel. As a result, I found that I cared little for the stakes of Steve Rogers and his treason. Instead, I wanted to continue to follow the women leading the other fronts of this battle. Their challenges each seemed appropriately massive and well-suited to their character strengths and flaws – particularly Riri Williams as the combination Ben Franklin and Paul Revere of Earth’s ragtag revolutionary defense.

Spencer writes his evil Captain America in the same way he would write a heroic one, and that wrings false. We are meant to believe this Hydra version of Captain America is identical to the one we know – a thorough, strategic, overachieving boy scout who can yell “Hail Hydra” and apologize to his lover for being a secret Nazi in the same breath.

You cannot have that narrative cake and eat it too.

If Spencer wants this event to have real heft, we’re going to have to break Steve Rogers out of being an evil boy scout and make him truly detestable – and that risks alienating a lot of readers who aren’t looking to be that challenged by Captain America when they could just turn on their TVs to see Chris Evans in action. If Spencer has been doing that in Captain America – Steve Rogers for the past year, it doesn’t show at all in this issue.

And, if he hasn’t, he’s doing this all wrong.

Buy Secret Empire #0 right now digitally or pre-order its hardcover collection, out this fall. For more on Secret Empire, see the Crushing Comics Guide to Marvel Events.

You state that you love Sam Wilson and he is “your” Captain America. Right after saying you’ve just browsed a few issues. So, what makes you love him and stand as “your” Captain America?

You have a good point – that comment from me is confusing!

I read the pre-ANAD Sam Wilson material and connected with it immediately, I was totally addicted. I’ve also loved him in ANAD Avengers. It just makes a lot of sense to me as a progression of his character, and that has been reflected in the ANAD Cap issues I’ve browsed, as well. We’ll see if that holds up when I do my full ANAD read.

Also, there’s been so much back and forth with Steve in the last decade (dead, alive, top cop, back to Avengers, aging, aging more, evil) that I’ve completely lost my connection with him as Cap. I don’t feel like there is any story left with him that I’m interested in reading. Sure, the right author could prove me wrong, but that sense of the lack of possibility with the character is a real turnoff. (I feel similarly about Hulk, but haven’t yet ready any of Cho Hulk.)