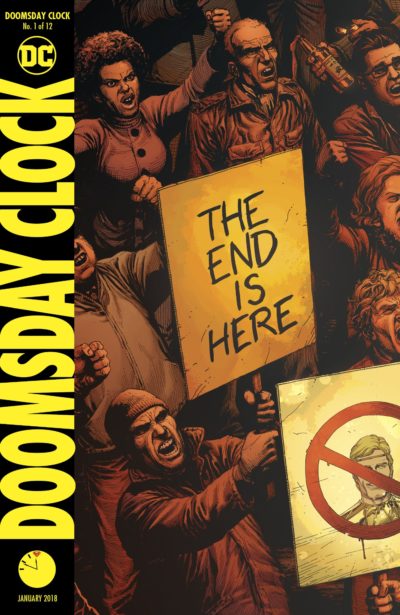

It is 2017, and every classic work of art or commerce is just another chance to launch a new franchise. Everything old is flogged again.

The Handmaid’s Tale is now an Emmy-winning television show that has extended its universe both before and after the story in the classic novel. The long-running Archie comics have been turned into a nonsensical thirst-trap of a TV show about sex and murder where it is every season of the year on every day to allow for a full range of fashionable costuming.

Classic franchises are groaning under the weight of being re-franchised. It’s franchising squared. Disney is determined to pump out Star Wars movies almost as frequently as they used to release Star Wars novels back in the day and Warner Brothers has rushed a Justice League into the theatres before we’ve had a chance to care about most of the individual heroes who would form it.

There’s even news that Amazon is planning to make an ongoing series out of Lord of the Rings, ignoring the extended fart sound that was made by the bloated Hobbit trilogy and the fact that they could simply serialize the original film series across two entire seasons if it was carved into TV sized chunks.

I’m trembling in anticipation for the “long awaited” adaptations of some of my favorite TV commercials and magazine ads.

(That is only halfway a joke.)

And here we are, revisiting Watchmen, one of the comic medium’s true masterpieces, because we cannot leave well enough alone.

Yes, we already had a Watchmen movie and a Before Watchmen, but they were each one-time events. This is more than an event. It’s also a mash-up with DC’s ongoing universe that we never asked for but cannot help but watch like rubberneckers delighting in a gruesome accident. (Which says nothing for the ethical concerns, addressed at length at ComicsBulletin.)

If anything can be forgiven of being a retread of past ground, shouldn’t Watchmen? After all, it was Alan Moore’s original idea to take a dead comics universe and put its characters through a meat grinder of a final story. He might have wound up using his own original characters in the end, but he’s just as culpable of re-franchising as any of these modern examples. Moore’s career is full of these examples – MiracleMan, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, and even Peter Pan. He loves digging up comics corpses to reanimate as much as films studios do!

And therein lies the truth of the matter. Moore always got a pass because his work was derivative but delightful. All of these franchise sins can be forgiven if the new extension of the franchise is good. The Handmaid’s Tale won that Emmy, after all, and everyone loves an Archie with abs.

Why not revive the Watchmen? Everybody’s doing it and they’ve been doing it forever – since long before Moore did it back in 1986.

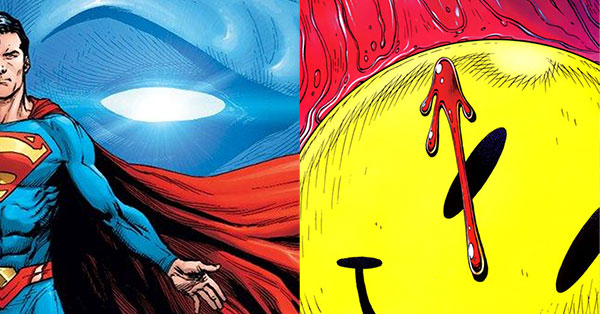

Doomsday Clock #1  & Watchmen #1

& Watchmen #1

Doomsday Clock #1 written by Geoff Johns, drawn by Gary Frank, and colored by Brad Andersen. Watchmen #1 written by Alan Moore, drawn by Dave Gibbons, and colored by John Higgins.

Doomsday Clock is not meant to be a slavish, panel-by-panel homage to Watchmen, but the parallels are clear.

Both issues open with similar narration. Both are largely contained in a 3×3 nine-panel grid structure, and this first issue of Doomsday Clock employs a similar rhythm of breaking the grid to Watchmen #1. Both issues end with a sudden scene change punctuated by a historic quote that is followed by illuminating back matter.

There is an additional storytelling parallel that Doomsday Clock #1 ought to have picked up from Watchmen #1. Watchmen included several scene transitions throughout the issue, though each one turned out to be an extension of Rorschach’s journey through the narrative.

The first scene change in Watchmen is the most significant. On page nine, we cut from Rorschach looking at the Comedian’s photo of the old Watchmen to that same photo hanging above Hollis Mason as he enjoys a beer with Dan Dreiberg. Their conversation reveals they are the two Nite Owls, old and new.

The scene could have existed elsewhere, but the transition immediately lends it additional context: some of the Watchmen are still alive, and some of their mantles were handed down to others.

A page later, we realize this story is still the story of Rorschach, who shows up unexpectedly in Dreiberg’s house as he returns. The implication is that Rorschach, too, was a Watchman – which also tells us that the membership has changed over time, pre-explaining the upcoming scenes with Ozymandias, Dr. Manhattan, and Silk Spectre.

For all his withering critique of society in his journal, Rorschach was once involved in protecting it. We immediately realize that, in a way, his pessimism is him bemoaning his own failures.

Doomsday Clock has just one cutaway from its primary narrative – a scene of the evacuations of the city. There’s much less room for unspoken context. Once the opening six pages of world-building end, we follow Rorschach straight through to the hard cut to Lois and Clark in bed at the end of the issue.

Doomsday Clock has just one cutaway from its primary narrative – a scene of the evacuations of the city. There’s much less room for unspoken context. Once the opening six pages of world-building end, we follow Rorschach straight through to the hard cut to Lois and Clark in bed at the end of the issue.

Rorschach is concerned with freeing a particular villain from prison under the cover of evacuation before a potential nuclear strike. She is Erika Manson – “The Marionette” – new to the world of Watchmen, but drawn from a Charlton Comics parallel just like most of Moore and Gibbon’s characters.

(She is also the parallel of a character recently used by Tom King in his Batman run just prior to The Button crossover, which cemented the story of outside inference in the DC timeline. Coincidence?)

Manson is our initial mystery in Doomsday Clock in the same way The Comedian was in Watchmen. “Why kill this one man,” we wondered as the issue pressed on and introduced us to more of the former team, “why does he matter?” “Are they all in danger?”

Why he matters and if the rest of the team is in danger is a thread that unravels the entire narrative.

We find ourselves asking the same thing about Manson. “Why this woman,” we wonder, “and how is it that she might ‘find god’?” Why is Rorschach initially resistant to bringing along her husband, The Mime, yet then so willing? Will his inclusion help or hinder finding god?

(We cannot help but assume the god to which Rorschach refers. After all, he is the living embodiment of the Doomsday Clock.)

In the course of Rorschach’s negotiation with The Marionette, we get another parallel to Watchmen #1: just as Dan Dreiberg was a new Nite Owl, we learn this is not our original Rorschach.

This revelation is almost lost in the issue. Rorschach pulls off a glove to show what seems to be a black- or brown-skinned hand, when The Marionette apparently knew his original hand to be white. The coloring of Doomsday Clock is such a shadowy, orange muddle that the reveal packs no punch. Only a page later, when we see his hand next to Manson’s white skin, does the reveal click.

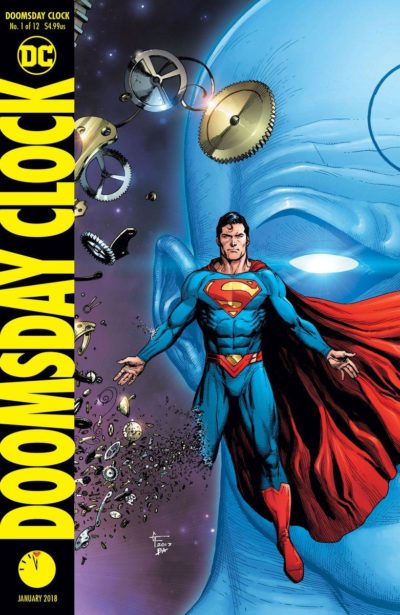

The coloring stumble is one symptom of a greater problem of the Gary Frank line work and Brad Anderson colors across the issue. They’re just too much.

Frank’s artwork is attractive and has many nods to Gibbon’s style, but often feels weighted with too much ink. Gibbons’ obsessedly-detailed panels were always ink-filled, but still had moments of seeming minimalism. Frank cannot stop piling on shading lines that are rendered moot by digital colors doing all of the shading for him. He drops as much ink on Manson’s neck as Gibbons’ did on Dr. Manhattan’s entire monotone blue body in order to lend it some sense of weight and dimension.

Anderson’s oversaturated coloring is hard to bear, so muddy it feels at points like it is sepia-toned. It’s not just the bungled reveal of Rorschach’s hand, but the onslaught of brown, orange, and gray in every panel. Everything feels oversaturated but nothing feels bright until the pop of Ozymandius’s costume and, later, the transition to the DC Universe proper.

That’s narratively effective, but it’s a heavy-handed device. Gibbons and Higgins achieved the same effect with Dr. Manhattan’s introduction even though they had already used many of the colors of that scene in their palette earlier in the issue.

(Perhaps the original also seemed lurid in its saturation back in the day; John Higgins’ original color work was almost blindingly bright with a heavy inclination to using primary colors.)

The heavy lines and muddy colors of Doomsday Clock only emphasize the claustrophobia of the narrative. We stick with Rorschach, The Marionette, and the Mime throughout the issue as they trek back into the heart of the city. The issue feel small, which puts the emphasis its decompression. There are two or three pages in the journey which are wholly unnecessary – they convey no unique information. They seem to exist purely because there is nothing else to take their place.

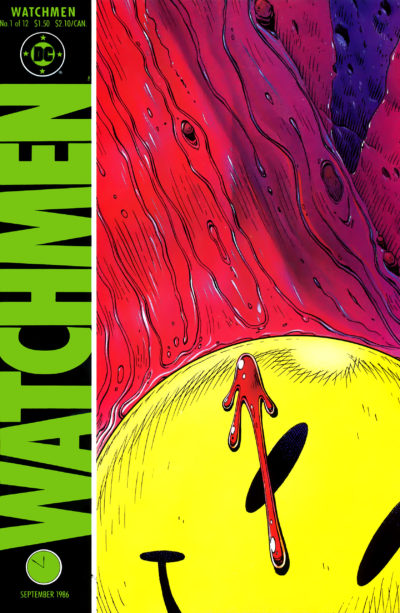

Watchmen was a social commentary, a puzzle box, and a murder mystery. Its first issue was paced deliberately to introduce us to the full scope of its city and its cast. The scene between Rorschach and Ozymandias in Watchmen #1 is especially heavy with portentous meaning that cannot be understood on an initial reading. Yet, we never feel that Moore and Gibbons are holding back. This is a complete chapter that only becomes more fulfilling as you learn more.

Watchmen was a social commentary, a puzzle box, and a murder mystery. Its first issue was paced deliberately to introduce us to the full scope of its city and its cast. The scene between Rorschach and Ozymandias in Watchmen #1 is especially heavy with portentous meaning that cannot be understood on an initial reading. Yet, we never feel that Moore and Gibbons are holding back. This is a complete chapter that only becomes more fulfilling as you learn more.

Doomsday Clock is also full of social commentary, though Johns’ version feels cartoonishly ham-handed in the present day. It’s also pregnant with moments where we are certainly missing the full context, but instead of being portentous they feel deliberately incomplete. We can feel Geoff Johns building a mystery by omission rather than by inclusion.

Now we come to the final pages. In both issues, they are examples of humanity, though that comes with a footnote in Doomsday Clock.

In Watchmen, Dan and Laurie head out to dinner together. They are able to shed their heroic mantles in a way that Rorschach and Dr. Manhattan cannot (and in a way the Comedian could not seem to enjoy). It’s subtle, but narratively important – a thread that will carry us through the closing frames of the story.

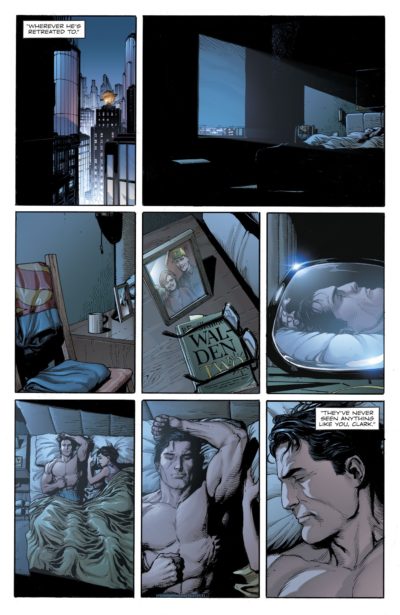

In Doomsday Clock, we are pulled through the window of Lois and Clark’s Metropolis apartment and into Clark’s nightmare remembrance of his parent’s death.

It’s a confusing turn if you haven’t been following DC Rebirth, and maybe even if you have been.

The Kents dying in a car crash was never an element of Superman’s mythology until the New 52 Superman in 2011. That Superman is dead, as of 2016, but in 2017 some elements of his memories and narrative were merged into the newly-returned classic Clark in the “Superman Reborn story.” Since that classic Clark has no history on this post-New 52 Earth, he might as well remember things the way its Clark knew them. There’s no other truth to be had.

Which Clark are we seeing here? It would make sense for it to be the current one, yet I’m not so sure. There is no hint of his son with Lois in the sparse decor of their Metropolis bedroom. Neither character seems to be wearing a wedding ring. And, the neatly-folded Superman costume draped over a chair seems to be the t-shirt and jeans look sported by the New 52 Superman.

(There is also his bedside copy of Walden Two, which merits a separate discussion entirely.)

Does it matter which version of Clark we’re seeing here? Maybe. If it is the classic Clark in the present day, he is being troubled by exactly the sort of difference in universes seemingly caused by Dr. Manhattan’s interference. If it is a flashback to the dead New 52 Clark, we could be seeing the very moment that a massive, invisible, blue hand reaches in and begins to tamper with reality.

That’s the sort of comic continuity muddle that Watchmen was more likely to satirize than include. Surely a modern Watchmen would include many jabs at alternate dimensions and altered memories, probably still using Dr. Manhattan as a device.

Will Johns use the deus ex machina of Dr. Manhattan to poke fun at the hands that steer all of these confusing, universe-altering acts of editorial interference, just as Grant Morrison inserted himself into his run on Animal Man? Or, will Doomsday Clock be an irony-free crossover that is totally self-serious in its presentation of Dr. Manhattan as a universal meddler?

Only the next 11 months will tell. No matter what they unfurl, they cannot change that Doomsday Clock #1 is a lackluster issue. It’s impeccably constructed but missing the scenes and smaller moments that made Watchmen #1 an unqualified classic even before its event came to a close. I don’t think the answer was to be be more slavishly devoted to the original – if anything, I think Doomsday Clock may have hewed too close to Watchmen without finding its own unique alchemy.

Seems rather harsh when you introduce it as it’s own piece while hating on comparison aspects thru out. Rate it on it’s own and try again. If your mood is it’s a speculative period piece vs watchman with no further context then your reviews are very unbalanced. I expected more from you.

I appreciate you sharing that critique of my review! I agree that there is discontinuity between the commentary in the intro and the style of the review. I try to write intros in a way that are more accessible to my non-comics readers, but in this case it doesn’t really introduce the idea of a comparison review very well at all. I definitely can do better.

.

However, if you are reacting purely to the star rating, you should know that 2.0 isn’t an unusually low or harsh score for me regardless of if I’m comparing one thing to another. I’ve read 1572 comics this year and my average score is 3.08. I treat 2.5 as “truly average.” I thought this book was a bit less than average, thus the score.