Earlier this year in a jaunty bit of Q&A with Twitter followers, my comic books colleague Adam from the Battle of the Atom podcast asked me the following question:

“Why do you hate the good stuff sometimes?”

Adam was mostly asking about comics, but this is a question that has followed me my entire life. Any of my friends who have gone to the movies with me has asked the same question.

Image by Yatheesh Gowda from Pixabay

It doesn’t matter what the thing is. You can hand me a random stack of anything: comics with no credits, new albums by unfamiliar artists, or even a selection of burger condiments. it’s all the same. I will enjoy a consistent amount of each sampling, and I will tend to prefer some of the unpopular stuff while eschewing some of the most most mainstream items.

I always thought this was because I have unique wiring in my brain. I thought it was that certain tropes or styles simply lack appeal for me.

I’m sure that’s true, to some extent, but I’ve recently learned that it might also be because I am a “harbinger of failure.”

I first heard about this concept last year while watching a 2017 episode of the British quiz show QI, or Quite Interesting, as gleaned from a 2015 MIT News article on a study conducted by two MIT professors. Here is how QI summarized it:

The difference between the next big thing and a turkey is that there are people who will always buy the turkey – as in the American showbiz term for something that flops commercially.

There is a kind of consumer called “harbingers of failure”, whose always buy a new product that later goes on to fail. Thus, people with a “flop affinity” are in demand from people in market research because they are good at predicting what products will go on to be unsuccessful.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology analyzed 10,000,000 transactions at a chain of convenience stores, and they found that people who buy the nail polish that fails are also the people who buy the ice cream that fails. Harbingers of failure in the past have also bought watermelon-flavored Oreo biscuits and a range of ready-meals made by the people who made Colgate toothpaste called “Colgate Kitchen Entrees.”

The moment I heard this explanation, I recognized myself in it.

More on that in a moment. First, let’s talk about the flipside of being a Harbinger of Failure: disliking popular things.

When you meet someone who consistently dislikes things that are popular, it’s easy to assume they dislike those things because they are popular. That’s an easy way lay claim to some vague, ineffable coolness, right? Dislike anything that reaches wide acclaim, because you are too special to enjoy popular things. Maybe you liked it better before it was popular, but not anymore.

At least, that’s the assumption a lot of us form when we meet someone who doesn’t like Game of Thrones, or Taylor Swift, or The Fast and the Furious, or Jonathan Hickman’s X-Men, or whatever other thing is surging through the critical zeitgeist at the moment.

I wish I could tell you my critical radar is as simple as that. Yet, more often than not, when I dislike those popular things the dislike occurred in a complete vacuum of popular opinion. And, similarly, when I like unpopular things, I fall in love with them long before I realize they’re unpopular.

My two clearest examples of this are both Wolverine.

When I started catching up on modern X-Men in 2010, I wasn’t spending any time consulting popular opinion on the books. The only comics community I was aware of at the time were the CBR X-Men Forums, and those people were vicious. I’d simply buy whatever book from 2000-2010 was next on my list if I could find it at the right price.

I was reading dozens of X-Men comics a week – sometimes three trades a day! I was reading as fast as I was building new comic guides.

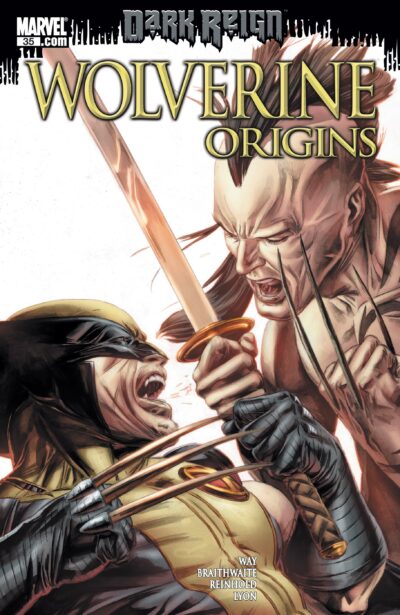

That is how I caught up on Jason Aaron’s Wolverine and Daniel Way’s Wolverine: Origins. Both runs were still active at the time. I had no idea whatsoever about the reception to either of them. They were books on my list and I was intent on checking them off.

I was immediate obsessed with Daniel Way’s Wolverine: Origins. So obsessed that every time I would finish a volume I’d order the next one from Amazon with 1-day shipping. I caught up to the present day over the course of a week while working on my Wolverine Guide. It was the best Wolverine story I ever read! It felt like the right scope for Logan and was full of surprising revelations about Logan’s history.

I loathed Jason Aaron’s Wolverine: Weapon X on first contact. Something about it made my eyes glazed over when I read every single word balloon. It was obsessed with its own violence. It was intent on forcing big plot beats that didn’t seem to fit Logan at all. I picked up several collections at once from the same seller, and they all made me wince as I read them.

Eventually, I made my way onto the internet to enthuse about Daniel Way and to commiserate about Jason Aaron. I was shocked, utterly and completely shocked, to discover the prevailing opinion was the complete opposite of mine.

People loved Aaron and despised Way.

It is my purest example of how I don’t like popular things and love unpopular ones, because I had no way of knowing ahead of time which would be which. Neither run had been cancelled. I wasn’t seeking out reviews because there was no question of that I would buy the books. I was clicking links right out of my newly-built guide and then clicking “BUY.”

Daniel Way’s Wolverine didn’t exactly fail – it ran for 50 issues and a tie-in book! But, it remains particularly unpopular, and I celebrate unpopular things like it’s my full-time job! Not just media properties like comic books and records, either. Just last month I had to buy out multiple grocery stores of a particular brand of vegan mayo that got suddenly discontinued. It was the best mayo I had ever tasted in my life.

I always assumed this because I take a chance on a wider amount of… well, everything, but in reading that MIT News article I started thinking about it in a slightly different way.

“These harbingers of failure have the unusual property that they keep on buying products that are taken from the shelves,” says MIT marketing professor Catherine Tucker, co-author of a paper detailing the study’s results.

Significantly, Tucker adds, these star-crossed consumers can sniff out flop-worthy products of all kinds.

“This is a cross-category effect,” Tucker explains. “If you’re the kind of person who bought something that really didn’t resonate with the market, say, coffee-flavored Coca-Cola, then that also means you’re more likely to buy a type of toothpaste or laundry detergent that fails to resonate with the market.”

Later, they add:

“You could think of it as preference for risk. People who are more willing to take a risk on an unusual product are more willing to take a risk in multiple categories.”

That is me to a tee.

I’m the person who reads 55% of all comics released in America because no one every recommends me the ones I wind up loving the most. I’m the person who stopped reading record reviews entirely and finds recommendation engines useless, because I have a better hit ratio if I randomly pick up things based on listening to 10 second clips.

While this wasn’t a stated part of the study, I think it also explains a certain distaste for popular things and flavors.

I think it also connects to our identity.

Image by Yatheesh Gowda from Pixabay

If you are hoovering up watermelon Oreos and coffee-flavored cola, the mainstream flavors like plain old chocolate might seem dull to you. If you always love a particular kind of little-seen, slice-of-life indie flick, the bombastic plot beats of a Jurassic movie might fall flat.

What happens when your entire model of consumption is based on being a harbinger of failure after failure? How do your preferences begin to change when every one of your favorite cookies gets discontinued and every one of your favorite TV shows gets cancelled early? Do you lean in to the failures even harder and champion them even more?

How does that shape you as a person? What if you spend decades being the only one you know who recommends the one-hit wonders and those strange flavors of breakfast cereal? Do your friends support you and sample your failed favorites? Or, do you become that friend, that weird inexplicable acquaintance always nattering on about something that seems fundamentally unlikable.

Thinking too hard about that can make me feel sad. No one sets out to be the person with unappealing tastes, no matter how many intangible cool points they can rack up from the experience.

Yet, part of it also energizes me. Being a harbinger of failure can be a special super power. Not everything that fails deserves to fail. There are many examples in the history of both art and technology of works of genius that weren’t fully appreciated until much later. What if I get to be the rare person who appreciated them for their time? What if it’s even more important that I understand how to describe and dissect art in its many forms so I can help more people connect with these fleeting products?

And, there is one final aspect to consider: no harbinger of failure is an island. We are an unlikely, unpopular legion. There is actualization and empowerment in connecting with someone who is the same sort of harbinger you are.

Why do I hate the good stuff sometimes?

Why do you not like the weird stuff sometimes?

Maybe we’re just wired that way.