My grandfather, Steven, with my beautiful Aunt Joyce and my grandmother, Florence, in her kitchen – all dressed for my parents’ wedding, October 1980.

My grandfather Steven was a gym teacher.

I never knew too much about him. My relationships have always gravitated towards the women in my life, and grandparents are no exception. I spent countless Sundays at the kitchen table with my grandmother, reading the Sunday paper. We watched Golden Girls together on Saturday nights. I would hover at her elbow every Christmas, awaiting my first ladle full of her Italian Wedding Soup.

My memories of my grandfather are more scant. He was retired. He would drive down to Florida and return with a Nintendo game for me, bought from a pawn shop – cartridge only, no instructions. He was genial beneath a gruff exterior, and I never once believed he was actually mean or angry with me. He liked baseball, which I still don’t, and The X-Files, I think, which gave me something to talk to him about when we would sit in my Aunt Susan’s sun room at family parties in the 90s.

.

My father Peter owns a gun shop. He managed bars and restaurants for decades. In his twenties he was a roadie for a band – lights, I think.

I know many facts about my father, but they are disconnected. They’re like a cloud that drifts through my memory, never quite coalescing into a specific narrative. He attended Central (my rival high school) and Temple (my rival college). (Funny, that.) He had a motorcycle accident in one of the roundabouts near the Art Museum that left his butt susceptible to numbness during long movies. He farms hot peppers in his spare time.

My memories of my father are many. He and my mother separated when I was three or four, but I saw him every week until I was eleven or twelve, and then every other week until school work made it impractical to spend alternate weekends away from home. I remember his old apartment with the low mattress, the bar where I spent countless Sundays watching Eagles games, and his first house with his now-wife with its bubble skylight windows off the master bedroom.

.

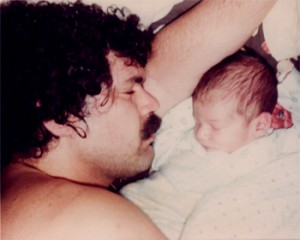

My father and I, fall 1981.

I will become a father sometime this summer. Or, I suppose, I am already. I am an account manager, a musician, and a writer.

I didn’t always know I wanted to be a father. I remember a specific point in my teenage years where – in a mix of angst and sudden, acute awareness of the world around me – I decided it would be irresponsible to bring anyone else into such an unfair and capricious world. But before that, I remember that I was always very concerned that I was my grandfather’s only grandson, and that I had to have children to continue our name to another generation.

E and I agreed a long time ago that there would be at least one child in our shared future, though the last name was (and continues to be) undecided. Over the years I’ve become accustomed to the idea. Much like our hypothetical eventual wedding would one day become reality, I knew that one day our hypothetical eventual child would arrive. I would joke with co-workers that she or he would be enrolled in military school at age three to combat all the various foibles of modern youth, but secretly I think I can solve those via limited screen exposure and regular listening to The Beatles.

(More on that, later.)

.

My grandfather passed away last Thursday. He was 87.

I don’t mention this in search of condolence. To lose him was a tragedy, but not a great surprise. At Christmas my three aunts told me it might be the last time I would see him, winking there from the end of the table.

He was my last living grandparent, including those in my still-new family-in-law.

The aunts brought pictures to his viewing on Sunday night. Old black and white photographs and pages from his yearbooks. I was struck by one photo of him, smiling from his wide face, hair black as pitch in a way I had never seen. On either side of him boys struggled up knotted ropes. Some of the boys were black, others white. The yearbook was from the early 60s.

I spoke at church on Monday morning, the same one where a much smaller version of me served as ring-bearer for Aunt Susan’s wedding. She and her husband picked me up the morning of the funeral and drove me to the cemetery after the services. Two men in crisp army uniforms awaited us there. They thanked us on behalf of our country and our president, and handed my father a flag folded thirteen times before one of them played the most beautiful and somber “Taps” I have ever heard in my life. I cried, finally, beside the headstone that he shares with my grandmother Florence.

I never knew my grandfather served.

At lunch after the burial my aunts and cousins took turns sharing somewhat apocryphal stories about him. He loved teaching people things. He loved cars – or, at least, driving – and aliens, and pointing out how people were “meatheads” and “nimblebrains” while subtly showing you what you were doing right.

He was alive for 31 years of my life – a decade over my next-oldest cousin – but I didn’t have a story to share, aside from those video games without instruction books. No tale from before I was born. No specific, outstanding memory, spurious or not. Nothing he had taught me that I could remember.

I don’t think that was his fault or mine. It was just life, and the years that separated us.

My father is now in his 60s. When our child is old enough to have memories he or she might really remember – those strong, crystalline memories – he will be in his 70s, much older than my grandfather was when I was that age. My father shared so many stories about my grandfather over the weekend, but none of them sounded familiar to me. Had I forgotten, or just never listened?

Now, our child will not have any great-grandparents, but will inherit a set of seven caring and altogether hilarious (and sometimes crazy) grandparents. I can’t say what my child will know or think about my father, among them. Some days I can’t even say what I think or know about him, though I am sure that I love him very much.

We called him a few weeks ago to set up our next dinner together, and to tell him about the baby – because waiting until the dinner would have been far too long. “Great news,” he said, smiling from the other side of the phone, and then asked me about my band.

Last Friday, while we discussed the funeral arrangements for his father on the phone, my father said, “I haven’t told the aunts about you and E and the baby – it’s your news to tell. I think maybe you should wait until after the funeral is over. But, earlier this week I did tell my father about it when I visited him. I didn’t think you would mind, or that he would tell anyone else. And now he won’t, I suppose. ”

“Thanks,” I said. “Thanks, dad.”