EV refers to the voice of Google Maps as, “The Map Lady,” and sometimes The Map Lady and I have a disagreement.

Case and point: to get to the zoo from my house, The Map Lady has me turn off of what is effectively the suburban version of Market Street to get onto Chestnut Street – which makes total sense – but then has me turn off of three-laned Chestnut almost a mile before a crucial left turn to return to sluggish one-laned Market.

On those occasions, I turn to EV during a stop at a red light and say, “The map lady is very confused, today.”

User Design versus User Experience, one of my favorite visual analogies from my time in start-up land. (Walkers have elected to cut through the grass rather than round the corner and walk on the pavers.) Photo by felixphs

Is she really? Computerized directions aren’t about a route that’s seemingly more direct or that has a higher speed limit. They’re taking into account a quantity and quality of factors that never occur to we humans as navigators … or even to the city planners who designed the streets in the first place!

Even though I call her confused, The Map Lady has found ingenious short-cuts to get me around Delaware County, like skipping a long chain of turn-only lights by cutting a three-quarter circle through a neighborhood with stop signs.

This amplifies the typical tension between User Design vs User Experience not only because of the sheer magnitude users, but also because the reality of their actions can transform the landscape itself.

This was exemplified for me by an article last month in Washington Post, “Traffic-weary homeowners and Waze are at war, again. Guess who’s winning?” A residential suburban neighborhood suddenly became a busy thoroughfare due to its status as a slightly more-efficient detour to construction than the route that was officially marked. Understandably, home owners who wanted to live in a quiet area aren’t too pleased with the increased traffic and noise.

While commenters castigated the home owners’ sense of entitlement (streets are public, after all), I couldn’t help but sympathize with them. I’ve only once lived on a block I’d consider a “thru-street” that delivered regular traffic from one destination to another. I find the noise distracting to everything I do, from recording to sleeping. When we bought this house, part of the search criteria was to find a street that more or less lead nowhere in an enclosed neighborhood. (Not a development; just a neighborhood that has no single street that starts on one side and continues out the other.)

Yet, during recent construction, SEPTA busses were detoured through the street perpendicular to ours; it was the only north-to-south way to avoid the construction for a mile in either direction. I was aghast – I had never in a million years assumed we’d be living adjacent to a bus route. Luckily, the change lasted on a few days. Had it been longer, I would have been legitimately agitating to move.

I ponder these things as The Map Lady steers me through previously unexplored territory to get to familiar places. She’s doing more than getting me there faster, or annoying another solitude-loving homeowner: she’s changing my use of physical infrastructure.

Is a tiny residential street built to handle occasional traffic able to endure the volume of “a vehicle every two seconds,” as was the case in that WaPo article? Are the driveways designed so that residents may safely exit into “a backup dozens of cars deep”? Should parking rules be changed, permits issued, stop signs turned to lights, or dotted or solid lines added to the road faces? The innards of historical cities like Philadelphia and Boston have long since wrestled with these dilemmas, but computerized mapping has made them relevant to every street in the country.

The rule of digital cartography can have impacts beyond rerouting traffic. Fusion details how a digital mapping company called MaxMind’s act of assigning unplaced IP addresses to the geographic center of the United States made life a nightmare for renters at an isolated Kansas farm. These people made absolute certain their street wouldn’t be mistakenly re-purposed as a thoroughfare when they rented their house, but didn’t plan for the ire of scores of scammed internet users landing on their front lawn – or for their personal information to be shared across the internet in misplaced retaliation.

Alternately, perhaps you live in a converted church and have suddenly discovered you are a Pokemon Gym courtesy of augmented reality game designer Niantic:

Living in an old church means many things. Today it means my house is a Pokémon Go gym. This should be fascinating.

— Boon Sheridan (@boonerang) July 9, 2016

This is what I’m a little leery of. People pulled up, blocking my drive way as they sit on their phones. pic.twitter.com/WpRbilk6g6

— Boon Sheridan (@boonerang) July 10, 2016

In all three of these examples – Waze, MaxMind, and Niantic – the affected residents were none the wiser of their property’s sudden change in status until they began to suffer the deleterious effects of the situation via the behavior of others. Worse, none of the three have an obvious avenue to protest their designation – Waze, by its nature, is crowdsourced and behaving as expected; it took inquiries from Fusion’s writer Kashmir Hill for MaxMind to make a change after a decade of ignorance to the problems they were causing; so far, Niantic offers no publicized process for property owners to opt out of their Pokémon Go mapping.

That is terrifying. The nature of our connected world is allowing private companies to effectively create their own geolocated “watch lists” that may soon begin to affect property values or put lives at risk without even the basic requirement of an appeals process.

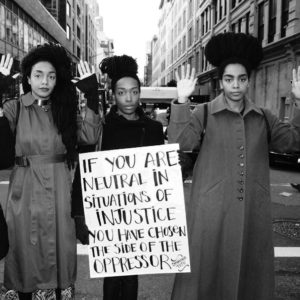

Also, note the aspect of privilege associated with these three cases. The Waze neighborhood waged war through the app and were covered by the Washington Post. The Pokémon Church Guy immediately caught on and his good-natured response turned his plight into massive Twitter exposure.

What about the residents of the Kansas farm? They arguably experienced the worst harm, “visited by FBI agents, federal marshals, IRS collectors, ambulances searching for suicidal veterans, and police officers searching for runaway children,” and having their personal details spewed across the internet in a series of doxxings. Until Ms. Hill found them all they got was a sign posted in their yard by the sheriff that said to leave them alone and call him with questions.

I won’t re-invade that shared personal information to find out their personal demographics, but even if they’re a third white male in this example the demographics of their location (and of the property’s owner, and 82 year old woman) combined with the length of their suffering speaks volumes.

Digital cartography is no longer simply describing or annotating our physical world – it’s having a reciprocal impact that is invisible until it’s unavoidable – and, even when it is unavoidable, its true nature is frequently gated by the technological access and savvy of the afflicted.

For me, that begs the question of which geography represents the truth – the one we can experience solely through the physical, tangible world, or the one that is exclusively digitally accessible? As with history, I think the truth will be determined by the victors, and in many cases that won’t be the unsuspecting residents like the people living in one of the houses in this story.

is a major shocker, because the vast majority of fans assumed Riri’s introduction in the pages of Invincible Iron Man (

is a major shocker, because the vast majority of fans assumed Riri’s introduction in the pages of Invincible Iron Man ( As War Machine, he’s lead his own title on many occasions (though they are usually short-lived) and he’s and been a significant character in both comics and now films (though he’s frequently sacrificed as a narrative reason to make Stark feel bad, as has happened twice this year alone).

As War Machine, he’s lead his own title on many occasions (though they are usually short-lived) and he’s and been a significant character in both comics and now films (though he’s frequently sacrificed as a narrative reason to make Stark feel bad, as has happened twice this year alone).