[Patreon-Nov16-Post-Bug][/Patreon-Nov16-Post-Bug]A long, long time ago, I wrote about how Built To Spill’s Keep It Like a Secret was the first crack in the dam I had constructed against enjoying music performed by men.

My 90s record collection was like a personal Affirmative Action policy on music. At the time, I didn’t even have the excuse of being a musical artist who was wielding judgement and harboring jealousy when it came to my male peers. Aside from Tom Petty’s Greatest Hits and the requisite Nevermind and Unplugged, I had nary a dude in my collection. The sound of the male voice didn’t please me, even if their songs weren’t of the dull “get the girl” variety.

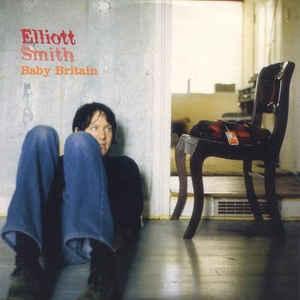

If picking up the Built to Spill record in February of 1999 was a crack in my dam, Elliott Smith’s XO was the flood that followed.Rarely in my life have I been so sucker-punched by a record as I was by XO, released the prior August. I first heard them both from the same source – my friend Anastasia, whose musical taste subsumed my own for a few months that year, transforming it completely for the rest of my life.

While the quaver of Smith’s voice and his delicate songs of defeat would worm their way into my brain over time, but it was when I hit track four that I knew I was in love with this album.

There is something about a song that starts abruptly with a vocal and clanging piano chords that makes me love it. Perhaps it’s a genetic disposition towards anything reminiscent of “Penny Lane.”

While “Baby Britain” doesn’t necessarily call back to that song, there’s an unmistakably 70s McCartney vibe to the bounciest of Smith’s songs from XO (which namechecks Revolver in its third verse). It helps that it straight up nicks the tiny, high guitar stabs from “Getting Better.”

The song is so relentlessly cheerful and major key that it takes several listens before you realize how tragic it is. (This is one of Smith’s singular talents.) It’s a song for a friend in a downward spiral – one Smith recognizes but doesn’t know how to steer out of. All that cheer is the good humor of someone halfway through the evening’s bottle of vodka; it won’t last until the bottom, and she’ll need another the next day to recover.

I’ve always adored the puzzle of the chorus – two incomplete thoughts that change the lens of the rest of the song depending on how you read them.

I’ve always adored the puzzle of the chorus – two incomplete thoughts that change the lens of the rest of the song depending on how you read them.

For someone half as smart

You’d be a work of art

You put yourself apart

And I can’t help until you start

Is the “someone half as smart” the Baby Britain Smith is singing to? If you read it that way, the entire song is a kiss off or a put down. I don’t. Nothing else in the song casts her as dim.

I’ve always read that first line as Smith’s dig at himself. If he didn’t know all of her destructive behavior so well he’d swear she was a work of art – an alchoholic manic pixie dream girl sailing across a sea of vodka. Sadly, he knows better than that. What’s charming to a man half as smart is a honeycomb of character flaws to Elliott.

It’s easy to hear the next line as “You pull yourself apart,” which entirely makes sense within the world of the song, but the lyric is “you put yourself apart” (calling back to “separated from the rest” in the first verse). Can Baby Britain’s problems be character flaws if some of them are so intentional? We’ve all met that person who creates their own tidal waves of conflict. It’s easy not to pity them when they’re the ones putting themselves apart from everyone else and the helping hands offered by that crowd, but that doesn’t mean you don’t feel sorry for the choices they make.

The final line is one of those perfect Elliott Smith lines. It’s a sentence of infinite density. If we were reading this grammatically, the “until you start” would seem to apply to the prior phrase. It doesn’t. It’s self contained. Smith applies so much compression to “And I can’t help you until you start to help yourself” that he’s stripped out every extraneous word. The chorus could just be this single elegant line repeated four times, but that would draw too much attention to it. Better a a the final line, a summation but also tossed away as the swell of the song crests into another verse.

Also, I humbly submit that this is one of the best lyrics ever written.

We knocked another couple back

The dead soldiers lined up on the table

Still prepared for an attack

They didn’t know they’d been disabled

Yet, with retrospect, the truly cutting lyric is the final line of the final verse. It’s another of Smith’s trademark compressed phrases, with a double negative obscuring the meaning until you squint at it closely.

Nothing’s gonna drag me down

To a death that’s not worth cheating

Who is Smith to pull Baby Britain out of her spiral of misery when it would be an admission that he could pull out of his own? That death is a fate that’s not worth cheating – either because it’s inevitable or because on some level he believes he might deserves it. Nothing can drag him down to that level or away from it because he’s already a permanent inhabitant.

I’ll always remember stepping into my mother’s car a few days after October 21, 2003 and saying, “I’ve got some awful news to tell you.” Elliott Smith’s music was something so intelligent and perfect, and to this day I mourn that there’s a finite amount of it in this work because he finally reached the end he couldn’t cheat his way out of.