[Patreon-Nov16-Post-Bug][/Patreon-Nov16-Post-Bug] Welcome to my “From The Beginning” read of Dr. Seuss’s entire bibliography!

Welcome to my “From The Beginning” read of Dr. Seuss’s entire bibliography!

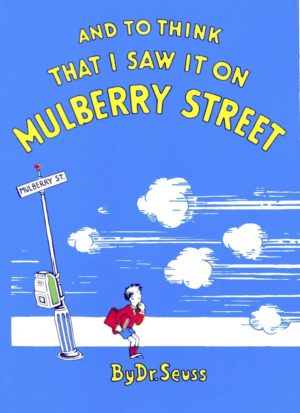

And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street was the second book released by the pseudonymous Dr. Seuss, and his first written explicitly for children.

(His first publication being his not-at-all sexual The Pocket Book of Boners, which was more of a joke book.)

![]()

And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street (1937) – Dr. Seuss

Gender Diversity: None – every single character depicted is male; one woman is mentioned

Ethnic Diversity: “Rajah” riding an elephant, a Chinese man eating with chopsticks

Challenging Language: keen, outlandish, minnows, charioteer, Rajah, fleet (adj), Alderman, confetti

Themes to Discuss: Truth vs Exaggeration, racial stereotypes

Reading Time: 5-10 minutes

Young Marco has a problem. Every day he walks to and from school, and every day his father asks him to tell him what he’s seen, but after he relates his tale his father always replies, “Your eyesight’s much too keen.”

This is a theme I can sympathize with, as EV has a keen memory of fine details. She will sometimes comment weeks after an event on a particular phrase or the color of the buttons on a shirt.

Marco’s problem is a bit different. You see, if he only notices his own feet and a horse-drawn wagon, it doesn’t seem like enough to report on to his father. Thus, the wagon is now pulled by a yellow racing zebra whipped into a frenzy by a charioteer.

I was cautious of this book on my first read. We’ve now reached the age where EV is beginning to exaggerate intentionally and we’re teaching her what it means for something to be true. I want to encourage her imagination while emphasizing the value of truth. And To Think I Saw It On Mulberry Street does exactly that – it suggests that you ought to engage every aspect of your imagination to create a fanciful tale, but that in the telling its best to relate on the truth of the matter.

The illustrations are quite tame as Dr. Seuss goes. They mostly depict only the action of one animal and its cart down the street from a fixed perspective, even if the processing behind the animal grows to be quite elaborate.

Also, there aren’t many fantastical things – the people are quite people-like and the animals are all real. It took me a moment to realize a pair of giraffes were just giraffes because I was so intent on figuring out how they connected to some future fanciful beast.

Also, there aren’t many fantastical things – the people are quite people-like and the animals are all real. It took me a moment to realize a pair of giraffes were just giraffes because I was so intent on figuring out how they connected to some future fanciful beast.

As with many early Seuss books, there is a casual racism employed in casting different racist tropes into obvious roles. Here were have a Rajah riding an elephant and “a Chinese man who eats with sticks.” Neither of these are caricatures or especially mean-spirited, so with some guidance on the trope I’d say they are still appropriate for modern readers.

While this book wouldn’t top my list of Dr. Seuss acquisitions, I think it has a worthy message and not too much confusing language, plus a pleasing rhyming scheme. Any kid who has spent time watching passing cars or telling you about their day will be able to relate.

I’ll be back next Wednesday with the second Dr. Seuss book, The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins!

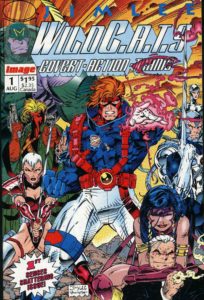

WildC.A.T.s played with the familiar “gifted one” trope of X-Men plus the alien conflict borne out in present day of Inhumans. From the start, Stormwatch was something much more nuanced even if it featured its fair share of X-TREME characters and powers and shoulder pads.

WildC.A.T.s played with the familiar “gifted one” trope of X-Men plus the alien conflict borne out in present day of Inhumans. From the start, Stormwatch was something much more nuanced even if it featured its fair share of X-TREME characters and powers and shoulder pads. How did Dr. Seuss go from writing on the topic of Boners to inventing one of the world’s most famous cats to writing an inspirational masterpiece like Oh, The Places You’ll Go? I intend to find out in this special edition of “From the Beginning,” in which I read the good doctor’s entire oeuvre in order.

How did Dr. Seuss go from writing on the topic of Boners to inventing one of the world’s most famous cats to writing an inspirational masterpiece like Oh, The Places You’ll Go? I intend to find out in this special edition of “From the Beginning,” in which I read the good doctor’s entire oeuvre in order. Was it any good?

Was it any good? My distinct impression has always been that Choi and Lee were superior storytellers without a good story. I know that sounds contradictory. What I mean is that they clearly made up an amazing universe and some compelling characters, but when it comes to plotting them through an arc there’s not a lot that’s memorable. I feel as though if someone just told them what situation to put the characters in (as Chris Claremont would do on his arc), the book would be great.

My distinct impression has always been that Choi and Lee were superior storytellers without a good story. I know that sounds contradictory. What I mean is that they clearly made up an amazing universe and some compelling characters, but when it comes to plotting them through an arc there’s not a lot that’s memorable. I feel as though if someone just told them what situation to put the characters in (as Chris Claremont would do on his arc), the book would be great. Lee was one of six Image founders. The other 1992 launches were:

Lee was one of six Image founders. The other 1992 launches were: